Showing posts with label Beginner. Show all posts

Saturday, April 11, 2015

How To Play Drums

The four drum patterns below make it easy to learn the drums progressively. They start out with just one part of the drum kit, and eventually include all the voices that make up a simple drum beat. This way you can learn how to play the drums with baby steps.

The Basic Drum Patterns

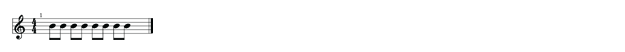

Take a look at the first exercise below. It has a single measure of eighth notes. The count is listed above each of the eight notes in the measure. The "x" symbol above the top line of the measure indicates that these counts are to be played on the hi-hats. Start by counting out loud (one and two and three and four and), and then play the hi-hats along with your counting. Loop this a few times, and focus on playing at a consistent pace.

In exercise two, you'll learn how to play the bass drum on the one and three counts. As you can see below, the bass drum is indicated with a solid note in the bottom space of the measure. You can watch the video lesson for tips on how to play the pedal with control.

Next, exercise three includes the snare drum on counts two and four. The snare drum is indicated by a solid note on the middle line of each measure. As with the bass drum, you want to focus on playing these right with the hi-hats. The strokes should line up perfectly, so it sounds like one complete sound.

Finally, exercise four brings everything together. The previous patterns were all leading up to this. As you can see below, this beat includes the hi-hats, snare drum, and bass drum - all together in one complete beat. This is how to play the drums in a real band setting.

Be sure you really focus on playing this beat steady and in time. It is highly recommended that you play along with a metronome - especially when first learning how to play on a drum set. Everything needs to sound even and consistent. Just loop the pattern over and over until you are feeling very confident.

If you are having any difficulty with this last beat, you can always go back and practice beats 1 - 3. That will help you focus on timing and limb-independence. Then, when you feel ready, come back to beat 4.

How to Play Blues Guitar For BEginners

The blues is kind of a hybrid between a major tonality and a minor tonality, so it’s like its own world. One of the best things about the blues is you can learn just a couple of small things and then jump in to playing and expressing yourself. If you learn to play the blues really well, you’ll have an excellent tool and color to use in your guitar playing, and when it’s appropriate, you can pull it up in other styles of music you play too.

There are a few things that it would be good for you to know before you start the Blues Guitar Quick-Start Series. We’ll be going through everything step-by-step, but it would be good if you know basic bar chords, basic power chords, the shuffle rhythm, note subdivisions, and hammer-ons and pull-offs. If you need to review any of these skills, you can check some of my other lessons.

It doesn’t matter if you play acoustic or electric in this series because everything we’ll cover is equally important for both types of guitar. The goal of this series is to make sure you’re familiar with the most important things you need to know for blues rhythm guitar and blues lead guitar.

We’ll start this series off by going through the blues 12-bar progression, and then we’ll learn some dominant seventh chords and how to apply them to the 12-bar progression. From there, we’ll dress things up a little bit by going through a couple of rhythm blues riffs to use with the 12-bar progression too. With everything you’ll learn in this series, the possibilities for your rhythm blues guitar playing can really only be limited by the amount of effort you put in and your own creativity.

Once we get the blues rhythm basics down, we’ll switch our focus to blues lead guitar. We’ll start by learning a shape for the blues scale. If you already know minor pentatonic scale this will be pretty easy for you because all you have to do is add one more note.

After you’re familiar with the blues scale, I’ll teach you how to start choosing your notes rather than just randomly playing through the scale shape. After that, we’ll look at turnaround licks and how they can be incorporated into your playing.

The guitar is an ancient and noble instrument, whose history can be traced back over 4000 years. Many theories have been advanced about the instrument's ancestry. It has often been claimed that the guitar is a development of the lute, or even of the ancient Greek kithara. Research done by Dr. Michael Kasha in the 1960's showed these claims to be without merit. He showed that the lute is a result of a separate line of development, sharing common ancestors with the guitar, but having had no influence on its evolution. The influence in the opposite direction is undeniable, however - the guitar's immediate forefathers were a major influence on the development of the fretted lute from the fretless oud which the Moors brought with them to to Spain.

The sole "evidence" for the kithara theory is the similarity between the greek word "kithara" and the Spanish word "quitarra". It is hard to imagine how the guitar could have evolved from the kithara, which was a completely different type of instrument - namely a square-framed lap harp, or "lyre".

It would also be passing strange if a square-framed seven-string lap harp had given its name to the early Spanish 4-string "quitarra". Dr. Kasha turns the question around and asks where the Greeks got the name "kithara", and points out that the earliest Greek kitharas had only 4 strings when they were introduced from abroad. He surmises that the Greeks hellenified the old Persian name for a 4-stringed instrument, "chartar". The earliest stringed instruments known to archaeologists are bowl harps and tanburs. Since prehistory people have made bowl harps using tortoise shells and calabashes as resonators, with a bent stick for a neck and one or more gut or silk strings. The world's museums contain many such "harps" from the ancient Sumerian, Babylonian, and Egyptian civilisations. Around 2500 - 2000 CE more advanced harps, such as the opulently carved 11-stringed instrument with gold decoration found in Queen Shub-Ad's tomb, started to appear.A tanbur is defined as "a long-necked stringed instrument with a small egg- or pear-shaped body, with an arched or round back, usually with a soundboard of wood or hide, and a long, straight neck". The tanbur probably developed from the bowl harp as the neck was straightened out to allow the string/s to be pressed down to create more notes. Tomb paintings and stone carvings in Egypt testify to the fact that harps and tanburs (together with flutes and percussion instruments) were being played in ensemble 3500 - 4000 years ago.At around the same time that Torres started making his breakthrough fan-braced guitars in Spain, German immigrants to the USA - among them Christian Fredrich Martin - had begun making guitars with X-braced tops. Steel strings first became widely available in around 1900. Steel strings offered the promise of much louder guitars, but the increased tension was too much for the Torres-style fan-braced top. A beefed-up X-brace proved equal to the job, and quickly became the industry standard for the flat-top steel string guitar.

At the end of the 19th century Orville Gibson was building archtop guitars with oval sound holes. He married the steel-string guitar with a body constructed more like a cello, where the bridge exerts no torque on the top, only pressure straight down. This allows the top to vibrate more freely, and thus produce more volume. In the early 1920's designer Lloyd Loar joined Gibson, and refined the archtop "jazz" guitar into its now familiar form with f-holes, floating bridge and cello-type tailpiece.

The electric guitar was born when pickups were added to Hawaiian and "jazz" guitars in the late 1920's, but met with little success before 1936, when Gibson introduced the ES150 model, which Charlie Christian made famous.

With the advent of amplification it became possible to do away with the soundbox altogether. In the late 1930's and early 1940's several actors were experimenting along these lines, and controversy still exists as to whether Les Paul, Leo Fender, Paul Bigsby or O.W. Appleton constructed the very first solid-body guitar. Be that as it may, the solid-body electric guitar was here to stay.

The sole "evidence" for the kithara theory is the similarity between the greek word "kithara" and the Spanish word "quitarra". It is hard to imagine how the guitar could have evolved from the kithara, which was a completely different type of instrument - namely a square-framed lap harp, or "lyre".

It would also be passing strange if a square-framed seven-string lap harp had given its name to the early Spanish 4-string "quitarra". Dr. Kasha turns the question around and asks where the Greeks got the name "kithara", and points out that the earliest Greek kitharas had only 4 strings when they were introduced from abroad. He surmises that the Greeks hellenified the old Persian name for a 4-stringed instrument, "chartar". The earliest stringed instruments known to archaeologists are bowl harps and tanburs. Since prehistory people have made bowl harps using tortoise shells and calabashes as resonators, with a bent stick for a neck and one or more gut or silk strings. The world's museums contain many such "harps" from the ancient Sumerian, Babylonian, and Egyptian civilisations. Around 2500 - 2000 CE more advanced harps, such as the opulently carved 11-stringed instrument with gold decoration found in Queen Shub-Ad's tomb, started to appear.A tanbur is defined as "a long-necked stringed instrument with a small egg- or pear-shaped body, with an arched or round back, usually with a soundboard of wood or hide, and a long, straight neck". The tanbur probably developed from the bowl harp as the neck was straightened out to allow the string/s to be pressed down to create more notes. Tomb paintings and stone carvings in Egypt testify to the fact that harps and tanburs (together with flutes and percussion instruments) were being played in ensemble 3500 - 4000 years ago.At around the same time that Torres started making his breakthrough fan-braced guitars in Spain, German immigrants to the USA - among them Christian Fredrich Martin - had begun making guitars with X-braced tops. Steel strings first became widely available in around 1900. Steel strings offered the promise of much louder guitars, but the increased tension was too much for the Torres-style fan-braced top. A beefed-up X-brace proved equal to the job, and quickly became the industry standard for the flat-top steel string guitar.

At the end of the 19th century Orville Gibson was building archtop guitars with oval sound holes. He married the steel-string guitar with a body constructed more like a cello, where the bridge exerts no torque on the top, only pressure straight down. This allows the top to vibrate more freely, and thus produce more volume. In the early 1920's designer Lloyd Loar joined Gibson, and refined the archtop "jazz" guitar into its now familiar form with f-holes, floating bridge and cello-type tailpiece.

The electric guitar was born when pickups were added to Hawaiian and "jazz" guitars in the late 1920's, but met with little success before 1936, when Gibson introduced the ES150 model, which Charlie Christian made famous.

With the advent of amplification it became possible to do away with the soundbox altogether. In the late 1930's and early 1940's several actors were experimenting along these lines, and controversy still exists as to whether Les Paul, Leo Fender, Paul Bigsby or O.W. Appleton constructed the very first solid-body guitar. Be that as it may, the solid-body electric guitar was here to stay.

This series will cover a lot of information, and it will be up to you to decide how far you want to take it. I feel that the blues is the style of music that crosses the most musical boundaries so it’s really important for you to get down really well. The stronger you get with playing blues music, the better the rest of your playing will be too, no matter what style you’re playing.

How To Use Vibrato

In this lesson, I’m going to help you kick your self-expression up another notch with a technique called the vibrato. Learning vibrato will really help you develop your own sound as a lead guitar player. Look at B.B. King for example. If you hear even just one note with his vibrato, you can tell right away that it’s B.B. King.

Just like a singer has their own natural vibrato with their voice, you’ll need to find and develop your vibrato sound. I believe that the best way to do this is to listen to your favorite guitar players and take note of how they use vibrato. Pull all the best parts from your favorite players and begin to make them your own, continuing to develop your own sound. For me, my favorite players for vibrato are Eric Johnson and Ty Tabor.

There are endless techniques for vibrato, so I’m going to show you the two ways that have worked best for me. Let’s start at the sixth fret of the B string using your pinky. The first technique for vibrato is like bending the guitar string up slightly, but over and over. Just like I showed you in the bending lesson, I have a little pivot between my thumb and my wrist.

The second way I want to show you I actually learned from Eric Johnson. When he does vibrato, he releases his thumb from the back of the guitar neck and uses his entire arm to push up on the string. In the video, you can see when I use this method my whole arm is working on the vibrato.

I honestly use both of these different methods to play vibrato, just depending on how I want the vibrato to sound. Try out both ways, experiment with how you want your vibrato to sound, and find what feels comfortable for you.

Vibrato is a very expressive technique, and there are two different elements of vibrato that you can use to change the mood or vibe of your music. The first element you can change is the speed of your vibrato, keeping it fast or slow to match the mood of your music. In the video, you can see that changing the speed of my vibrato makes a big difference in the overall sound.

The second element that will help you develop your voice with guitar playing is the width of your vibrato. Your vibrato can be narrow and subtle, or very wide across the fretboard. You can choose how wide you play your vibrato depending on the moment, and depending on how you want to sound.

Vibrato is a very personal technique, and there’s no right or wrong sound to it. Experiment with this technique to figure out what works for you and how you want to develop your vibrato. Pull up any of the jam tracks to practice with, and have fun trying it out. Watch the video to see an example of my vibrato to the minor scale jam track.

Basic Picking Technique

In this lesson about basic guitar picking techniques, we’re going to start with some universal picking tips, downstrokes, and upstrokes. Once you have those mastered, we’ll put them together and try alternate picking.

As a newer guitar or lead guitar player, I recommend starting with a medium, regular shaped pick. Get a feel for that pick first, and then decide if you want to go with a different pick based on your personal preference. I like a thicker pick myself, but experiment to find what works best for you.

The first universal tip I want to give you is to relax. I see many new guitar players tense up because they are focusing so hard on their picking. If you notice yourself tensing up, take a moment to shake it out. Staying relaxed will help you avoid injury and keep your picking efficient.

The next tip to keep in mind is avoid locking your wrist while you pick, otherwise you’ll be picking from your elbow. Playing from your elbow can possibly lead to injury and cause inefficient playing. Be sure to keep your wrist loose and relaxed.

Often, I see new guitar players use big sweeping motions from the elbow when picking, but by focusing on picking from your wrist, you’ll be able to keep your motions nice and small. Pick the string just enough to make a sound. By using efficient motions, your pick will always be right there, ready to play another note.

When gripping your pick, it’s subjective to personal preference. Start by placing your thumb on the pick, and come down on the pick with your finger. Depending on what’s comfortable for you, your fingers may end up being curved in or more straight, but it doesn’t matter as long as your pick grip is comfortable for you.

Picking angle is another area where technique is subjective. Most guitar players angle the pick downward, some use a flat or parallel angle, and I’ve seen some who angle the pick upwards. Play around with different angles to find what works best for you.

Now let’s start practicing the downstroke. Start with the high E string and push down just enough to make the string sound. Keep practicing your downstroke, and don’t forget to practice your downstroke on every string. Each string will feel a bit different, and it may take days, weeks, or even months to feel really comfortable here.

I should also mention here that while practicing your downstrokes, you should figure out where you want to hit the strings. I keep my hand pretty close to the bridge, and I end up hitting the strings right around the middle pickup of my guitar.

As part of your guitar lessons, you’ll need to practice upstrokes. Keeping your wrist loose and remembering to keep your movements small and efficient, pull up on the string just enough to make a sound. Upstrokes will probably take more practice than downstrokes for you to get comfortable with them, and that’s okay. Just be sure to practice on each of the strings.

Once you’re comfortable with both downstrokes and upstrokes, it’s time to combine the two into a technique called alternate picking. That means you’ll follow an ‘up down up down up down’ pattern of picking all the way through. This is where those small efficient motions really become important. Again, practice alternate picking on all six strings because each string feels different.

Practicing these skills with a metronome will help your progress and your overall sense of time. If you don’t have a metronome, there are lots of websites with free apps, or you can use an app on your phone like I do. Don’t start out setting your metronome too fast though. Instead of speed, your first goal should be to make your picking clean and even. A good speed to start with is 70 beats per minutes.

This kind of practice can be tough, but is well worth it. Exercises like these will take you from an average guitar player to a guitar player that people notice because of your skill and timing. I still practice my picking all the time to keep my skills sharp.

How To Play Lead Guitar For Beginners

This series is perfect for anyone new to playing lead guitar, and great for those already playing lead guitar but are unsure what to practice next.

I’ll show you techniques specific to each hand, and teach you the most important scales. Then we’ll go through specific techniques like legato, hammer-ons, pull-offs, bends, and vibrato. I’ll share tips to make your solos sound awesome, and we’ll even go through your first solo, tying everything in the Lead Guitar Series together.

As a bonus, I’ll be including real music for you to practice with as we go. That will be much better than just practicing with a metronome!

In this lesson we’ll focus on your fretting hand, and the first tip I have for you is to simply relax. If you feel any tension along your shoulders, arms, or hands, shake it out and get comfortable before starting to play again.

Now let’s look at hand posture for playing lead guitar. Pretend you’re holding a baseball in your hand – that’s the easiest way to have good hand posture. Now move your hand to the guitar, put your thumb on the back of the neck, and then place your fingers on the fretboard.

Good basic finger posture is to come down on the strings with the very tip of your finger, the same way you would when you’re making a chord, and be sure to place your fingers right behind the fret so there’s no extra buzzing noise when playing. Keep your thumb along the back of the neck as a starting point, at least until we get into other techniques.

For the scales you learn in this series, we’ll be using the designated finger concept. This means you’ll have a finger dedicated to notes played on a particular fret. If you were playing a G major scale, you would get any notes along the second fret with your first finger, any notes along with third fret with your second finger, and so on.

The last tip is another simple one: keep your fingernails short. When my fingernails grow longer, it’s harder to hold the notes with the tips of my fingers, plus my nails dig into the fretboard.

Keep these basic tips in mind to help you out as we move through the remaining lessons. Now I have to remind you, you probably won’t sound like an all-star lead guitarist as soon you start these lessons. The important thing is to practice consistently, using the real music I supply in each lesson.

Dynamic Strumming Tips For Beginners

In this lesson, I’ll give you a couple of tips for dressing up your strumming pattern. Playing the basic strumming patterns we learned in lesson nine, Essential Strumming Patterns, is great but they can get a little mundane at times.

One thing you can do to change things up is hit just a single bass note. A general guideline to get started with this is to hit the lowest root note of whatever chord you’re making. Instead of strumming the whole G chord for the first down of the down down up strumming pattern, you could hit just the low G note on the third fret of the sixth string, and then finish the strumming pattern normally.

It can be difficult at first to get your accuracy good enough to hit just a single bass note. Try looking at the sixth string in this case and practice hitting it accurately and consistently. Once you have that done, you can throw in the rest of your strumming pattern.

You can try this tip with all of your chords. For example, instead of strumming the whole open C chord, you can strum the lowest bass C note which is the third fret of the A string. All you need to remember is that your lowest root note should be your bass note. After you’re comfortable with hitting just the bass note, you can throw more notes in with it as well.

This same idea can apply when you’re playing bar chords too. If you were playing an A bar chord, you would just get used to hitting the lowest root note of the chord. Go through all the chords you’ve learned in the Rhythm Guitar Quick-Start Series and apply this idea to them. It may take time to develop this and get your picking accuracy down, but that’s okay. Check out the video to see how a 1 4 5 progression would sound using this technique along with the jam track.

The next technique we’ll go over to add more life into your strumming is muted strums. It’s easier for me to show you what it is first rather than explain it, so take a look at the video to see muted strums.

Essentially a muted strum means that I am actually muting the strings with the fleshy part of my strumming hand as I come down on a particular strum. Using my hand to mute the strings right as I strum through the strings gives a very percussive sound. The idea behind this technique is to make the same sound as a snare drum.

If you’re playing in 4/4 time throwing in a muted strum on beats two and four can give you a great percussive sound. It almost makes it sound like a drummer is playing with you. In the video, I play an example with the down down up strum, using a muted strum on beats two and four. Your muted strum doesn’t always have to be on beats two and four, but it can be whatever beats you like as long as it fits the music you’re playing.

Once you get this muted strum technique down, you can combine it with the single bass note technique. Let’s take our down down up pattern and apply both techniques. You can hit a single bass note for your one, a muted strum for your two, and then upstroke will be a full upstroke.

This is one idea you can use, but you don’t have to use it every single time you play. You can use this pattern on beats one and two, and then use your regular strumming pattern on beats three and four to create a new strumming pattern.

Pull up the drums only jam track for this lesson and work on getting these two techniques down. If you have to stick with the same chord throughout the whole thing, that’s totally okay. Once you’re comfortable with these two techniques, then you can throw in some chord changes too.

Develop your Timing And Feel

In this lesson, we’re going to continue to focus on your strumming by developing your timing and feel. This is a critical area of musicianship that is important for you to develop. If you have good timing, people will enjoy listening to you and they’ll enjoy playing along with you. If your timing isn’t good, people won’t enjoy listening to you as much and they’ll be frustrated if they play with you too.

One of the key elements to developing your timing is practicing with a metronome. You can use the jam tracks I have supplied here as well, but it’s important to have a constant beat to help keep you on track. Sometimes guitar players don’t realize they have timing problems until they get into a situation where it’s really obvious and embarrassing for them. Don’t let that be you! Work on your timing and really get it down.

I’m going to teach you a great exercise for developing your timing and feel, and you need to be familiar with note subdivisions to play through the exercise. The subdivisions I’m talking about are quarter notes, eighth notes, eighth note triplets, and sixteenth notes. For this lesson we’ll use a jam track that is just drums at 70 beats per minute. If you want to use a metronome instead, that’s okay too.

This loop is in 4/4 time and you’ll be able to count along with it the same way I do in the video. Those numbers are the quarter notes, which are the basic beat and pulse. You can strum along with the quarter notes using all downstrokes or alternating down and upstrokes. Either way, being able to follow a beat is the first step following this exercise and developing your timing.

Listen to the drumbeat in the jam track, try to lock in to be right on beat, and have all your strums spaced evenly. Check out the video to see me play a sample, and then work on this exercise until you feel very comfortable staying on the beat. You can also pull out a metronome to practice locking in on the beat at different tempos. One tip for you here is that moving another part of your body like nodding your head or tapping your foot can help you stay in time.

The next step in our exercise is to switch from quarter notes to eighth notes. If you’re not familiar with eighth notes, you’re essentially taking quarter notes and doubling the amount of strumming you’ll do. Quarter counts are counted by ‘1, 2, 3, 4,’ where eighth notes are counted by ‘1, and, 2, and, 3, and, 4, and,’ which doubles your strumming.

When you transition from quarter notes to eighth notes, there’s a chance you’ll start dragging behind or rushing ahead of the beat, so make sure to keep listening for the beat. Keep yourself locked into the beat and make sure your strumming is still evenly spaced.

When you start playing eighth notes, I’d recommend alternating upstrokes and downstrokes as it’s easier to keep up with the beat. In the video, I play an example starting with quarter notes, switching to eighth notes, and going back to quarter notes. As you try it, you can stick with each subdivision for as long as you like.

If you’ve made it this far with me on this exercise, you’re doing a great job. Now we’re moving to the tricky part of the exercise, eighth note triplets. Eighth note triplets are three evenly spaced strums per beat. If you’ve never counted triplets before, it can be a bit tricky. It’s counted as ‘1-trip-let, 2-trip-let, 3-trip-let, 4-trip-let,’ meaning there are three syllable for each beat.

If you’re having trouble playing eighth note triplets, you can spend some time just tapping it out like I do in the video. Another thing you’ll need to watch out for is not accidentally playing two short notes and a long note, but still keeping your strums spaced out evenly.

Since you have three strums per beat, note that you’ll start with a down up down on the first beat and the next beat will up down up. Because three is an odd number, one beat will start on a down stroke and the next beat will start with an upstroke.

Let’s add this triplet to our exercise. Go through quarter notes for as many measures as you like, switch to eighth notes, and then go to eighth note triplets. When you switch to the triplets, you’ll probably have some rushing or dragging, but that is normal at first since the triplets have a much different feel from the other subdivisions. In the video, you can check out how it will sound from my example.

The final subdivision in our exercise is sixteenth notes, and you’ve probably already guessed that sixteenth notes are four evenly spaced strums per beat. Sixteenth notes are counted as ‘1-e-and-a 2-e-and-a 3-e-and-a 4-e-and-a ’ giving us four distinct syllables for each beat.

if this is tough for you to play at first, just try tapping it out like I do in the video. Once you’re comfortable with these sixteenth notes, we want to add them to the exercise. Play through quarter notes, eighth notes, eighth note triplets, sixteenth notes, and then work your way back down to quarter notes. Remember that moving your head or tapping your foot to the beat will help you keep time. Check out the video for my sample of this exercise with sixteenth notes added in.

The point of this exercise is to help you be aware of the beat and be able to switch between subdivisions in a moment’s notice. If you can get this down, it will sharpen your rhythm and set you apart from a lot of other guitar players.

I know this is a lot of information, so don’t feel pressured to have all these subdivisions down in one exercise. You can start out with just quarter notes and eighth notes, and after you’re comfortable with those you can add in eighth note triplets. Once you’re comfortable with eighth note triplets, then you can add in sixteenth notes.

Strumming Patterns For Rhythm

In this lesson, we’re going to go through some of the most essential strumming patterns you need to know as a rhythm guitar player. These strumming patterns are the fundamental building blocks that you will use to build a lot of your strumming patterns in the future. If you can get these down really well, learning other patterns later will be much easier.

Some of these patterns will seem simple to you but it’s important to get each of these patterns down well. We’ll be using the same drum jam track from the last few lessons to practice with. Before we jump into strumming patterns though, I want to go over a few strumming technique tips with you.

The first tip I have for you is to relax. Try not to tense up, because your playing will not sound fluid and you’ll get tired easily if you are tense while you strum. The second tip I want to give you goes hand in hand with that, which is to not lock your wrist and strum from just your elbow.

Keeping your wrist relaxed means your playing stays fluid and you won’t get tired as easily. An easy way to think about this is to pretend you have something stuck on your finger and you’re trying to flick it off. If you try that movement now or watch me in the video, you’ll see that the elbow is still moving but most of the motion is coming from the wrist.

The first strumming pattern we’ll look at is a basic eighth note pattern that uses all downstrokes. In case you’ve never counted eighth notes before, I’ll teach you how to do that quickly. Usually in a song, there’s an underlying pulse that you can clap along with. In the video, I count out a few quarter notes, followed by some faster eighth notes.

Essentially the key with the eighth note strumming pattern is to keep our downstrokes even and in time. This may seem like a simple pattern, but it’s a good place to start to develop your timing and get a feel for the guitar.

For all the strumming patterns in the rest of the lesson, I’ll use an open G chord. Check out the video to see me demonstrate the eighth note pattern along with the jam track.

The next strumming pattern that we’ll look at is also an eighth note pattern, but instead of just downstrokes, we’ll alternate both downstrokes and upstrokes. Lots of newer guitar players have trouble with their upstrokes, so I’ll give you two tips to help you out.

The first tip is when I use a downstrokes, I generally hit all six strings. When I use an upstroke, I’m usually only hitting the top three or four strings. Don’t feel pressured to hit all six strings with your upstrokes.

The second tip I have for you is don’t dig your pick too far into the strings on your upstroke, otherwise it could be too hard to get your pick through the strings. Just use enough of the pick to make the strings ring out in a volume that matches your downstroke.

If you follow along with my counting in the video, you’ll see that on the numbers you would use downstrokes, and on the ‘ands’ you use upstrokes. You can also see me play this pattern along with the jam track.

Now let’s take this eight note strumming pattern up a level by putting some accents in with it. Being able to put accents into any of your strumming patterns is a valuable skill to have. I’m going to through this same pattern, but I’m going to accent the second and fourth beats, which are both downstrokes. On these strokes, you’ll dig into the strings a bit more and highlight those strums the way a drummer would accent his beats. You can see and hear what I mean as I add accents to this pattern with the jam track in the video.

Using accents in a classic strumming pattern like this is a great way to customize your sound to whatever song you’re playing. If you’re using sheet music, you’ll be able to tell that a strum should be accented if there is an arrow above the tab or chord.

The next strumming pattern is a little more involved, but is still based on a regular eighth note strumming pattern. I call this one the down-down-up strumming pattern, and it brings in a concept called the Constant Strumming Technique. This technique is when you keep your eighth note strumming going even if you aren’t actually digging into the strings with the pick on one of your strums.

As you watch me demonstrate in the video, the Constant Strumming Technique becomes more clear. The basic counting for this pattern is ‘one-two-and’. You’ll see that my arm keeps going with the eighth note beat, but I didn’t actually hit the strings with the pick on the first ‘and’ upstroke. Try this short pattern over and over again until you get it.

That’s the basic down-down-up strumming pattern, which you can do over beats one and two, and beats three and four. The trick is to keep your strumming arm going even when you don’t dig into the strings. You can see this strumming pattern with the jam track in the video. Learning how to leave strums out of eighth note or sixteenth note strumming patterns is an important skill to have.

Our last strumming pattern to go over is a sixteenth note pattern. If you don’t know how to count sixteenth notes, we’ll go over that quickly for you. Sixteenth notes are four equally spaced strums over each beat. The way to count sixteenth notes is one, e, and, a, two, e, and, a, three, e, and, a, four, e, and, a. We’ve got four syllables for the four strums contained in each beat.

This may seem simple to you, but there is a lot more strumming going on in a sixteenth note strumming pattern, so don’t let the pick fly out of your hand and remember not to tense up as you strum. Start out slowly, and if you need to, you can use a metronome and lower the tempo while you work on your strumming. Feel free to throw in some accents while you strum too. Check out the video to hear how it sounds with the jam track.

Now that you’ve seen these fundamental strumming patterns, it’s important to start practicing with the jam track using your open chords, power chords, and bar chords.

Play Open Chords For Beginners

So far in this series, we’ve gone over power chords, bar chords, and how to move them all around the fretboard, but no rhythm guitar series would be complete without some open chords. In this lesson, I’m going to teach you the most essential chords you need to know as a rhythm guitar player.

Bar chords and open chords often go by the same name, yet they sound very different. In the video, the G bar chord and the open G chord each have a distinct sound. Not only do they sound different, but they can also be played in different spots on the fretboard. Depending on what you’re playing, you may want to use a bar chord some times and an open chord at other times. It’s important for you to know both types of chords so you have more options and more freedom when playing guitar.

The opens chords we’re going to play during this lesson are G major, C major, D major, E major, E minor, A major, A minor, B, and F. You already kind of know the F and B chords because I’ll be teaching you the bar chord shapes. It’s important to include those chords since they’re in the same area of the fretboard as your open chords. If you’re already comfortable with these chords, that’s fine, but you should still watch the entire lesson because I’ll be giving you some tips on playing clean sounding chords and having smooth transitions.

This will be a lot of information, so don’t feel like you need to have all these chords down before you move on to other things. Instead, take one or two at a time, work on them, and then bring them into your daily practice routine. Once we go through all these open chord shapes, we’ll apply them to a few popular chord progressions that we went over in the previous lesson.

The first chord we’ll learn is an open G chord, and I’ll show you two different fingerings. The first one uses your first, second, and third fingers and the other uses your second, third, and fourth fingers.

Going through the first one, you’ll put your second finger on the third fret of the low E string, your first finger on the second fret of the A string, and then your third finger on the third fret of the high E string. This is an open G major shape and you can strum all six strings of this chord.

The second fingering you can try is playing the same notes with your second, third, and fourth fingers. Using this fingering for the G major chord makes it is easier to change to an open C chord, which is a very common change.

The second open chord shape we will learn is a C major chord. Put your first finger on the first fret of the B string, second finger on the second fret of the D string, and your third finger on the third fret of the A string. When you play a C major, don’t worry about strumming the low E string, as it should be left out.

Lots of new guitar players can have trouble with this chord shape because they can’t quite reach the third fret of the A string with their third finger. If that’s the case for you, make sure you have good posture with your hand. If you bring your elbow down closer to your body, it puts your hand in a better position to grab that note.

The next chord we’ll learn is open D major. Put your first finger on the second fret of the G string, your second finger on the second fret of the high E string, and your third finger on the third fret of the B string. When you strum the D major chord, just strum the top four strings, leaving the low E and A strings out.

One problem that newer guitar players can have with this chord is that their fingers are sitting so close together in a small space that they end up muting the strings around them. You’ll notice that your third finger can easily mute the high E string if you’re not aware of it. In order to avoid this problem, make you’re playing on the very tips of your fingers.

The next chord shape we’ll learn is the open E major chord. If you’ve already learned bar chords from earlier in this video series, then you already know the shape. Put your first finger on the first fret of the G string, your third finger on the second fret of the D string, and your second finger on the second fret of the A string. You can strum all six strings for the E major chord. This is another chord where your fingers might be too close together and accidentally mute other strings, so make sure you’re playing on the tips of your fingers.

One tip I want to give to help switch between chords smoothly is to make sure that you know the chord shapes you’re using really well so you can go right to them. Be comfortable with making each shape before even trying to switch between chords.

The next chord we’ll look at is the open E minor chord, which is really easy once you know E major chord. If you make an E major chord shape, all you have to make an E minor chord is take your first finger off of the G string. An easy way to practice your E minor chord is to work on switching between the E major and E minor chords.

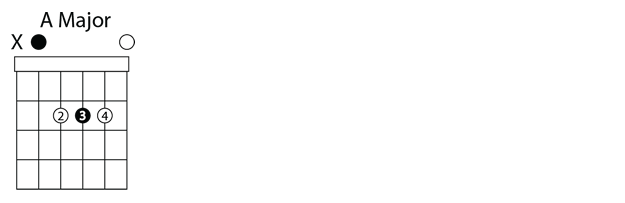

The next chord to learn is A major, and if you’ve learned your bar chords, you’ll know this chord already. Put your first finger on the second fret of the D string, your second finger on the second fret of the G string, and your third finger also on the second fret of the B string. You have to really scrunch your fingers together to get them all in the second fret, and when playing this chord, you leave the low E string out.

Another tip I want to give you for smoother transitions between chords is to anticipate the next chord. It helps to visualize and feel your next chord before you actually need to change to it. If I’m switching between an E major and an A major, and I know I have about two bars before I need to switch to A major, I should be thinking about what that chord looks and feels like. This tip prevents you from being surprised by the next chord and accidentally missing it.

Next, we’ll learn the open A minor chord. Once again, if you know your bar chords, you know we’re taking our A major shape and just changing the fingering position slightly. Put your first finger on the first fret of the B string, your third finger on the second fret of the G string, and your second finger on the second fret of the D string. When you strum the open A minor chord, leave the low E string out. To remember the A minor chord, know that it is shaped just like the E major chord shape, but it’s moved over one string set.

The next chord we’ll look at is F major, and like I mentioned earlier, we’ll use a bar chord for this one. Use your index finger to make a bar across all six strings on the first fret, then put your second finger on the second fret of the G string, your fourth finger on the third fret of the D string, and your third finger on the third fret of the A string.

Make sure your bar is placed right behind the fret, using the bony edge of your finger rather than the soft middle part. If you want to make this F major an F minor chord, all you have to do is take your second finger off the G string.

The last chord we’ll go over is B major, and this will also be a bar chord. Place your bar on the top five strings on the second fret, and put your second finger on the fourth fret of the D string, your third finger on the fourth fret of the G string, and your fourth finger on the fourth fret of the B string. If you want to turn this B major chord into a B minor chord, just switch your three fingers making the A shape into an A minor shape.

Try to relax as much as you can when playing these chords. If your guitar seems like it’s really hard to play, you may want to have your guitar set up by a professional. It’s inexpensive and it can make your guitar play as easily as possible.

Take the time to get these shapes down. Don’t expect to be fully comfortable with them overnight or even over a couple of weeks, and don’t try to tackle too many at once. Also remember not to try switching between chord shapes until you have each individual shape down, otherwise you might get frustrated.

Once you have these chords down, you can start to apply them to the common chord progressions we went over in the last lesson. Instead of playing a 1 4 5 progression with bar chords, you can try using open chords instead, like G-C-D. You can also try a 1 5 6 4 progression using open chords, which in the key of G would be G-D-E minor-C. Using open chords will give a different sound, and knowing them gives you options you can choose depending on the kind of sound you want to portray.

Now it’s time to practice these open chords to real music, so pull up your jam track for this lesson. It’s basically just the drum loop you can use to practice these chord progressions with your open chords. You can play the 1 4 5 progression, the 1 5 6 4, or you can use any of the 6 of the chords in the key of G major that you know from this lesson, G A minor B minor C D or E minor. The seventh chord in a major key is a bit of an oddball out, so don’t worry about that one for now. You can focus on the other 6 chords and try mixing them to come up with your own chord progressions.

The Basic Common Chord Progressions

In this lesson, we’re going to put the bar chords you’ve learned to use by playing through some of the common chord progressions that you’ll see as a rhythm guitarist.

Being able to use your bar chords to play through the more common chord progressions will be really useful when you are jamming with your friends, learning a song you don’t really know, or playing a church gig.

I won’t go too far into the theory of this yet, but I want to make sure you have some basics down first. For this video, we’re going to be in the key of G, which means the G note is our tonic, home base, or root note.

We’ll cover three basic chord progressions. The first is the 1 4 5 (or I-IV-V), the second is the 1 5 6 4 (or I-V-vi-IV), and the third is the 2 5 1 (ii-V-I). These numbers refer to the chords in a certain key, so be aware that every major key has seven chords you can choose from that occur naturally in that key. Those chords are represented by the numbers one through seven.

We’re going to use the four bar chords you’ve learned in the previous lessons to play though these chord progressions. It may seem difficult at first, but stick with me through the video and by the end it will start to make more sense to you. Closer to the end of the lesson, you’ll see that moving your bar chords around through chord progressions is quite valuable since you’ll be able to play in any key you want.

This is one of the most powerful concepts you can learn as a rhythm guitarist, so don’t feel pressured to get all of this down the first time through. You can come back and work through this lesson as many times as you need to.

The first chord progression we’ll learn is the 1 4 5, and we’ve actually already done this in the Rhythm Guitar Quick-Start Series by working on our G-C-D chord progression. Just know that this is a 1 4 5 chord progression, and when you’re in a major key, the 1 4 5 chords will all be major chords.

We start with the 1 chord, and because we’re in the key of G, we will start with a sixth string E shape G major bar chord. The 4 chord is a C chord, so instead of jumping around the fretboard, just move over to the A shape bar chord with the third fret of the fifth string giving the C root note. Our 5 chord is a D, so we’ll need to move our bar up to the fifth fret of the A string.

Play through the G-C-D progression until you get those changes down. It may take you a while to get it sounding smooth, but that’s okay. You also want to listen to this chord progression and memorize what it sounds like too.

The next chord progression we’ll work on is the 1 5 6 4, which is a really popular chord progression you can hear in all types of music. You’ll notice that we’re using three of the chords from the last lesson, but the order is different this time around.

We start on the 1 chord again, making a G chord with our E bar chord shape, but instead of moving to the 4, we’ll go right to the 5. We’ll make a D bar chord using the fifth string shape on the fifth fret. For the 6 chord, we’ll move to the E note on the seventh fret of the fifth string and make an E minor bar chord. It’s good to note here that the 6 chord in a major key will always be minor. Next is the 4 chord, and that will be our C bar chord using the A shape.

Go through this chord progression as much as you need to get the flow down. It may not sound great at first, but you’ll get to know exactly where to go for this chord progression. Listen to the sound of this progression too, memorizing the sound you hear.

The last chord progression we’ll go over is the 2 5 1, and while this progression is most commonly known for jazz music, it is used in all kinds of music. I’m sure you’ve noticed this is the only chord progression we’re going over that doesn’t start on the 1 chord, but starts on the 2 chord instead.

In a major key the 2 chord is always a minor chord, and since we’re playing in the key of G now, we need to make an A minor chord. We’ll use our E minor bar chord shape on the fifth fret of the sixth string for the A root note to make our 2 chord. The next chord is a 5, which in the key of G is a D. For the D major bar chord, you can keep your bar on the fifth fret and just move to an A major bar chord shape. For the 1 chord, you’ll go back to your G major bar chord on the third fret.

Spend some time working on the movement of those chords, getting the transitions down, and listening to how this chord progression sounds compared to the others.

That wraps up the three essential chord progressions for this lesson, so now comes the real magic of bar chords. You already know bar chords are movable, but what’s great about using bar chords in progression is that the progressions are now movable too.

I can play a 1 4 5 in the key of G using the G root note on the third fret, but if I want to play that same progression in the key of A all I have to do is move the home base or root note by playing an A major bar chord on the fifth fret. If I now play those same bar chord shapes relative to where I start, I’ll be playing a 1 4 5 in the key of A major.

I didn’t even have to think about it because all I had to do was memorize this shape and shifting pattern relative to where I started. You can do this in any key you want. If you wanted to play a 1 4 5 in the key of C, all you have to do is change your starting point to a C by playing a C bar chord shape on the eighth fret. This is helpful when you want to jam with your friends but you don’t know the song very well or you have to read a chord chart.

I’ve made a new jam track for you to practice your progressions and moving them around. It’s similar to the track you’ve already been using, but the bass and piano have been taken out so you can play any progression you want. This track is like a glorified metronome. It’s more fun to play with a drum track than just a clicking metronome. I’ll play through all three progressions in the video so you have an idea of what you can do.

How to Play Minor Bar Chord Shapes

In this lesson, we’re going to learn two different shapes for minor bar chords. These are really important to learn because in lesson seven you need to know these minor bar chord shapes so you can play through some of the more common chord progressions. These minor bar chord shapes should be easy for you to learn because they’re based off the two major bar chord shapes that you learned in the last couple of videos.

To get started, we’ll use our six-string E bar chord shape as our base, putting it on the fifth fret to make an A bar chord. To turn this into a minor bar chord, all you need to do is change one note. Simply take your middle finger off, and that changes this A major into an A minor bar chord.

Practice this a few times, while trying to remember all the tips I’ve given you to keep your chords clean sounding. You’ll notice when I take my middle finger off the string, it naturally comes back to help my index finger with the bar, making it a bit easier.

Basically, we just took an E major bar chord shape and turned it into an E minor, except we used a bar instead of open chords. Just like all the other bar chords you’ve learned, you can move this shape anywhere along the fretboard. You can look at your sixth string notes as a reference to find out which minor bar chord you’re playing.

If I move my bar up to the seventh fret and look at the note on the sixth string, I know this bar chord is a B minor using the E minor shape. Like always, try moving this shape around and remember that the name of the specific bar chord you’re playing comes from the lowest root note on the sixth string.

The next minor bar chord shape that we’ll look at comes from the open A major chord you learned earlier. Put the A major bar chord shape on at the seventh fret. This will be an E major bar chord because the root note on the seventh fret of the fifth string is an E.

Just like the last shape we learned, we only have to change one note, although this one isn’t quite as easy since we’ll have to change the fingering. The note you’re playing with your pinky on the ninth fret needs to move down to the eighth fret, and of course your pinky can’t move that way.

Instead, your middle finger will come back to the eighth fret of the B string, your third finger will grab the ninth fret of the D string, and your pinky will grab the ninth fret of the G string. Leaving the low E string out, this is the shape for your A minor bar chord. Since your index finger is on the seventh fret, this is an E minor chord using the A minor shape.

Get that shape down and then just like you did with your other bar chord shapes, practice moving it all around the fretboard. If you have trouble memorizing this shape, an easy way to remember it is to think of your sixth string root note major bar chord. It’s the same shape with your middle, third, and fourth fingers but the shape is moved over one string set.

Changing from the major bar chord to the minor bar chord is a good way to think about it. First get comfortable changing back and forth between the two, and then begin moving all around the fretboard. You can use the on-screen graphic again to reference the notes on the fifth string to see what chord you’re playing.

How To Play Major Bar Chord Shapes

Before learning the new chord shape, take a look at the graphic on-screen to see the names of the notes on the A string. Those are going to be the root notes for this bar chord shape.

We’re going to start learning this shape by making an open A chord, because that’s the foundation of this bar chord. Just like the other bar chord you’ve learned, we need to make this shape with our second, third, and fourth fingers. All three fingers will be on the second fret, with your second finger on the D string, third finger on the G string, and fourth finger on the B string. Leave the low E string out, and strum just the top five strings. This will feel different from what you’re used to, so it may take a bit for it to seem natural.

Once you’ve got that shape down, you need to come down with your index finger to make a bar right on the nut of the guitar. Take time here to get used to the whole shape and how it feels.

When you’re comfortable with the shape, move your bar up to the third fret and make your bar chord shape. Remember all the tips from video four about making a good sounding bar. Make your bar right behind the fret, come down with the bony edge of your finger, and adjust your bar vertically on the strings to get the cleanest sound.

When I’m making a five-string bar chord like this, I won’t always fret the sixth string, but my index finger will brush up against the string to mute it in case I accidentally hit it while strumming.

After your bar is in place on the third fret, come down on the strings with your second, third, ad fourth fingers to make the rest of your A shape. Now play the top five strings, leaving the sixth string out.

Once you’ve tried it, ask yourself if your bar chord sounded clean or if it sounded a little dead. If it was sounding dead or muted, double-check yourself. Make sure you’re coming down on the strings with the tips of your fingers and make sure your bar is strong behind the fret.

With this shape, you can train yourself in a couple of different ways again. Try putting your bar on first, followed by the rest of the shape, and then do the opposite by making your shape first and then the bar. Eventually, you’ll be comfortable enough to make this bar chord all at once.

After you’ve mastered this bar chord shape, you can try an alternate way of making it. You can use your third finger like a mini bar to hit all three strings in the A shape. It feels a little different and is a bit harder, but it’s another fingering method you can try out.

Play with this shape and practice by moving it all around the fretboard. Remember that the lowest note you play on the fifth string with your index finger is where you’ll get the specific name for each bar chord you’re playing. By getting familiar with the graphic on-screen you’ll know that a bar on the third fret makes a C bar chord, while being on the fifth fret would make a D bar chord.

Once you’re comfortable with this bar chord shape, you’ll need to start mixing it up with your sixth string shape, the E major bar chord. Just like the power chords we learned, this will keep you from having to jump all the way up and down the fretboard. As an example, playing a G-C-D progression on only the sixth strings means I’m moving around a lot. By using both sixth and fifth string bar chords, you see in the video that I have an easier time playing that chord progression.

You’ll need to get comfortable moving from the E shaped bar chord to the A shaped bar chord. That back and forth switch is a really important change every rhythm guitarist should have down. Using sixth and fifth bar string bar chords keeps you from jumping around the fretboard too much and helps you play a lot more efficiently.

Be sure to take enough time getting comfortable with each shape though before trying to switch between them. If you rush switching between bar chords before you’re ready, you’ll cause yourself a lot of frustration. Once you really have the shapes down, it will be easier to switch between them.

Now you need to apply this to some real music, so you can pull up the jam track for this lesson again. It is a G-C-D progression, and it’s one measure for each chord. You can keep it simple by playing a whole notes and concentrating on making your chords and changes well, or you can play quarter notes for every chord. You can check out my example of playing with the jam track in the video.

The guitar is an ancient and noble instrument, whose history can be traced back over 4000 years. Many theories have been advanced about the instrument's ancestry. It has often been claimed that the guitar is a development of the lute, or even of the ancient Greek kithara. Research done by Dr. Michael Kasha in the 1960's showed these claims to be without merit. He showed that the lute is a result of a separate line of development, sharing common ancestors with the guitar, but having had no influence on its evolution. The influence in the opposite direction is undeniable, however - the guitar's immediate forefathers were a major influence on the development of the fretted lute from the fretless oud which the Moors brought with them to to Spain.

The sole "evidence" for the kithara theory is the similarity between the greek word "kithara" and the Spanish word "quitarra". It is hard to imagine how the guitar could have evolved from the kithara, which was a completely different type of instrument - namely a square-framed lap harp, or "lyre".

It would also be passing strange if a square-framed seven-string lap harp had given its name to the early Spanish 4-string "quitarra". Dr. Kasha turns the question around and asks where the Greeks got the name "kithara", and points out that the earliest Greek kitharas had only 4 strings when they were introduced from abroad. He surmises that the Greeks hellenified the old Persian name for a 4-stringed instrument, "chartar". The earliest stringed instruments known to archaeologists are bowl harps and tanburs. Since prehistory people have made bowl harps using tortoise shells and calabashes as resonators, with a bent stick for a neck and one or more gut or silk strings. The world's museums contain many such "harps" from the ancient Sumerian, Babylonian, and Egyptian civilisations. Around 2500 - 2000 CE more advanced harps, such as the opulently carved 11-stringed instrument with gold decoration found in Queen Shub-Ad's tomb, started to appear.A tanbur is defined as "a long-necked stringed instrument with a small egg- or pear-shaped body, with an arched or round back, usually with a soundboard of wood or hide, and a long, straight neck". The tanbur probably developed from the bowl harp as the neck was straightened out to allow the string/s to be pressed down to create more notes. Tomb paintings and stone carvings in Egypt testify to the fact that harps and tanburs (together with flutes and percussion instruments) were being played in ensemble 3500 - 4000 years ago.At around the same time that Torres started making his breakthrough fan-braced guitars in Spain, German immigrants to the USA - among them Christian Fredrich Martin - had begun making guitars with X-braced tops. Steel strings first became widely available in around 1900. Steel strings offered the promise of much louder guitars, but the increased tension was too much for the Torres-style fan-braced top. A beefed-up X-brace proved equal to the job, and quickly became the industry standard for the flat-top steel string guitar.

At the end of the 19th century Orville Gibson was building archtop guitars with oval sound holes. He married the steel-string guitar with a body constructed more like a cello, where the bridge exerts no torque on the top, only pressure straight down. This allows the top to vibrate more freely, and thus produce more volume. In the early 1920's designer Lloyd Loar joined Gibson, and refined the archtop "jazz" guitar into its now familiar form with f-holes, floating bridge and cello-type tailpiece.

The electric guitar was born when pickups were added to Hawaiian and "jazz" guitars in the late 1920's, but met with little success before 1936, when Gibson introduced the ES150 model, which Charlie Christian made famous.

With the advent of amplification it became possible to do away with the soundbox altogether. In the late 1930's and early 1940's several actors were experimenting along these lines, and controversy still exists as to whether Les Paul, Leo Fender, Paul Bigsby or O.W. Appleton constructed the very first solid-body guitar. Be that as it may, the solid-body electric guitar was here to stay.

The sole "evidence" for the kithara theory is the similarity between the greek word "kithara" and the Spanish word "quitarra". It is hard to imagine how the guitar could have evolved from the kithara, which was a completely different type of instrument - namely a square-framed lap harp, or "lyre".

It would also be passing strange if a square-framed seven-string lap harp had given its name to the early Spanish 4-string "quitarra". Dr. Kasha turns the question around and asks where the Greeks got the name "kithara", and points out that the earliest Greek kitharas had only 4 strings when they were introduced from abroad. He surmises that the Greeks hellenified the old Persian name for a 4-stringed instrument, "chartar". The earliest stringed instruments known to archaeologists are bowl harps and tanburs. Since prehistory people have made bowl harps using tortoise shells and calabashes as resonators, with a bent stick for a neck and one or more gut or silk strings. The world's museums contain many such "harps" from the ancient Sumerian, Babylonian, and Egyptian civilisations. Around 2500 - 2000 CE more advanced harps, such as the opulently carved 11-stringed instrument with gold decoration found in Queen Shub-Ad's tomb, started to appear.A tanbur is defined as "a long-necked stringed instrument with a small egg- or pear-shaped body, with an arched or round back, usually with a soundboard of wood or hide, and a long, straight neck". The tanbur probably developed from the bowl harp as the neck was straightened out to allow the string/s to be pressed down to create more notes. Tomb paintings and stone carvings in Egypt testify to the fact that harps and tanburs (together with flutes and percussion instruments) were being played in ensemble 3500 - 4000 years ago.At around the same time that Torres started making his breakthrough fan-braced guitars in Spain, German immigrants to the USA - among them Christian Fredrich Martin - had begun making guitars with X-braced tops. Steel strings first became widely available in around 1900. Steel strings offered the promise of much louder guitars, but the increased tension was too much for the Torres-style fan-braced top. A beefed-up X-brace proved equal to the job, and quickly became the industry standard for the flat-top steel string guitar.

At the end of the 19th century Orville Gibson was building archtop guitars with oval sound holes. He married the steel-string guitar with a body constructed more like a cello, where the bridge exerts no torque on the top, only pressure straight down. This allows the top to vibrate more freely, and thus produce more volume. In the early 1920's designer Lloyd Loar joined Gibson, and refined the archtop "jazz" guitar into its now familiar form with f-holes, floating bridge and cello-type tailpiece.

The electric guitar was born when pickups were added to Hawaiian and "jazz" guitars in the late 1920's, but met with little success before 1936, when Gibson introduced the ES150 model, which Charlie Christian made famous.

With the advent of amplification it became possible to do away with the soundbox altogether. In the late 1930's and early 1940's several actors were experimenting along these lines, and controversy still exists as to whether Les Paul, Leo Fender, Paul Bigsby or O.W. Appleton constructed the very first solid-body guitar. Be that as it may, the solid-body electric guitar was here to stay.

How To Play Bar Chords For Beginners Tutorial

The first thing you need to do is get your finger across all six strings to make your bar, but the closer you get to the nut of the guitar, the harder it will be. Instead, start at the third fret and put your finger across all six strings to make the bar.

We’re going to go over three things about bar placement to help make your bar chords sound clean. First, when you make a bar, you don’t want to come down on directly with the fleshy part of your finger. Instead, tilt your finger back just a little bit so that you’re using more of the bony edge of your finger. This will make it a bit easier to get a good sounding bar.

The second tip for bar placement is how close your finger is to the fret. If you place your finger towards the middle or back of the fret, the bar chord will end up sounding very buzzy. The closer you are to the fret, the easier it will be to get a good sounding bar.

The third tip for bar placement is very specific to each guitar player. Everyone has creases in their fingers in different spots, so you’ll need to play around with your bar and move it vertically across the strings to find the best place to put your finger. If the creases of your finger fall on a string, it will be hard to get that string to sound clean.

Now that we’ve taken a look at those bar placement tips, we’re going to talk about bar technique. What you want to do first is form a clamp with your index finger and your thumb. If your thumb is in front of or behind your finger, it’s going to be hard to get the strength you need for a good sounding bar. Basically, you want to clamp the neck of the guitar between your index and thumb.

The next thing to be aware of with bar technique is if your wrist is kinked too far in either direction. If your wrist is kinked upwards behind the guitar neck, it will be too difficult for you to get a clean sounding bar. If your wrist is kinked too far in front of the guitar neck, your wrist will get really sore and start to hurt after a while. What you want to do is start off with a neutral position, and my wrist naturally ends up being curved forwards a bit, but not too far.

This next tip will help you keep your wrist in a good position. If your elbow is up in the air far away from your body, it will be hard to get a good bar because you’re not getting a very good angle on the strings. If you pull your elbow into your body, it’s automatically going to line your finger up with the fret and put you in a better position to make your bar.

Remember all these tips as you put your bar on. Strum your bar chord and see if it sounds clean. If it doesn’t sound clean yet, readjust it and go through all the tips I’ve given you.

You’re also going to want to experiment with how much pressure you need to make your bar sound clean. You don’t want to overexert yourself by putting too much pressure on, plus that can make the strings sound sharp. Use just enough pressure to get a clean sound from your bar chord.

Let’s work on strengthening your bar now that you have some tips to work with. The best way to start is by simply making a bar on the first fret and moving it up the neck one fret at a time. Use the tips I gave you to make small adjustments if your bar chord is not sounding clean.

As you practice, if you find that your index finger is too weak to make a strong bar, you can use your middle finger to help your index make the bar. You can think of it as a stepping-stone to making clean bars. Eventually your index finger will be strong enough on its own.

You’ll want to work on this for several weeks to develop your index finger strength. It’s normal for it to take a while to build up finger strength and dexterity, but that’s normal. Consistent practice will really pay off when it comes to bar chords.

Once you’re feeling good about your finger strength, the next step in bar chords is learning how to make an open E shape with your second, third, and fourth fingers instead of your first three fingers. The open E shape will be your second finger on the first fret of the G string, your pinky on the second fret of the D string, and your third finger on the second fret of the A string. This might feel a little awkward at first, but practice this until your fingers can go right into place.

Once you can make that shape, the next part of the bar chord is to get come down on the nut of the guitar with your index finger. This is the full shape of the bar chord you’re learning. Once you’re comfortable with that, you can bring the bar chord over by placing your bar across all six strings of the third fret and making the E shape with your other fingers.

You can see that you use the movable bar as if it were the nut of the guitar. By moving the bar chord and placing your index finger across all the strings, you’re able to make that bar chord shape.

Now there’s two ways for you to work on getting this shape. You can put the bar down first and then finish with the rest of the shape, or you place the shape on first and finish with the bar. It’s a good idea to practice both initially, as it really helps get your fingers and your brain used to the shape. Eventually you’ll want to be able to place the whole shape all at once.

Bar chords get the their name the same way power chords do, all depending on where the shape is on the fretboard. The name comes from the lowest root note played by your index finger on the sixth string. Just like power chords, bar chords are movable. If you look at the note names on the low E string, you can move this bar chord shape anywhere on the fretboard to play any bar chord you want. You can follow along with the graphic in the video to learn the notes on the sixth string.

The guitar is a popular musical instrument classified as a string instrument with anywhere from 4 to 18 strings, usually having 6. The sound is projected either acoustically or through electrical amplification (for an acoustic guitar or an electric guitar, respectively). It is typically played by strumming or plucking the strings with the right hand while fretting (or pressing against the fret) the strings with the left hand. The guitar is a type of chordophone, traditionally constructed from wood and strung with either gut, nylon or steel strings and distinguished from other chordophones by its construction and tuning. The modern guitar was preceded by the gittern, the vihuela, the four-course Renaissance guitar, and the five-course baroque guitar, all of which contributed to the development of the modern six-string instrument.

There are three main types of modern acoustic guitar: the classical guitar (nylon-string guitar), the steel-string acoustic guitar, and the archtop guitar. The tone of an acoustic guitar is produced by the strings' vibration, amplified by the body of the guitar, which acts as a resonating chamber. The classical guitar is often played as a solo instrument using a comprehensive fingerpicking technique. The term fingerpicking can also refer to a specific tradition of folk, blues, bluegrass, and country guitar playing in the US.

Electric guitars, introduced in the 1930s, use an amplifier that can electronically manipulate and shape the tone. Early amplified guitars employed a hollow body, but a solid body was eventually found more suitable, as it was less prone to feedback. Electric guitars have had a continuing profound influence on popular culture.

The guitar is used in a wide variety of musical genres worldwide. It is recognized as a primary instrument in genres such as blues, bluegrass, country, flamenco, folk, jazz, jota, mariachi, metal, punk, reggae, rock, soul, and many forms of pop.Classical guitars; also known as Spanish guitars are typically strung with nylon strings, plucked with the fingers, played in a seated position and are used to play a diversity of musical styles including classical music. The classical guitar's wide, flat neck allows the musician to play scales, arpeggios, and certain chord forms more easily and with less adjacent string interference than on other styles of guitar. Flamenco guitars are very similar in construction, but are associated with a more percussive tone.

In Portugal, the same instrument is often used with steel strings particularly in its role within fado music. The guitar is called viola, or violão in Brazil, where it is often used with an extra seventh string by choro musicians to provide extra bass support.