Showing posts with label Guitar Technique. Show all posts

Sunday, April 12, 2015

Rockers Technique = Metal Riffs

I major thriad chord progression on key C. This is not essential, you can use different, but there is same idea on every chord progression that hope you figure out soon.

--------------------------------

--------------------------------

------------------------5-5-5-5-

2-2-2-2-5-5-5-5-7-7-7-7-5-5-5-5-

2-2-2-2-5-5-5-5-7-7-7-7-3-3-3-3-

0-0-0-0-3-3-3-3-5-5-5-5---------

now this is like an verse of our rhytm guitar from that long haired heavy metal freak on the back. and its E5, E5, E5, G5, G5, G5, G5, A5, A5, A5, A5 and C5, C5, C5, C5 So lets get to the business and start to think our beginner riff for it? Oh yeah.

Thing is, that you can use all those notes that you see on tab above on current chord to riffs. Also we have other choice, you can use scales to make more complex riffs. But lets check first what we get when use those notes above.

-------------------------------

--------------------------------

--------------------------------

----------------------------5---

----2-------5-------7---3-3---3-

0-0---0-3-3---3-5-5---5--------

Use alternate picking if you want to play fast, its the only way, start slow improve accuracy and speed over time. Playing fast riffs, require very systematic and patient training.

I think you can find out that those notes should be played along the rhythm? Hehe just kidding, but keep that in mind and use your improvisation and you will make many different sounding riffs even from above one.

Alright, lets take something more and we take pentatonic scale to help our mission to make uber cool riff. Now you can use little trick, and check using guitar chord tool and check how each chord from chord progression tool show up. And now we talk about minor and major things here.

We use trick that we do same as above, but add a little. Look first tab and check those power chords there. When we add one more note to those power chords as you can see on chord name tool, they change to minor, major, sus, dim, aug depends what note we add. For example E5 we add open G string it turns E minor.

Allright, now we use those notes to conform the chord progression we see on chord progression tool. It says,

C Dm Em F G Am Bdim

as we used chord progression iii, V, vi, I its Em, G, Am, C we add the first G note to our E5 riff part. I used 1th string 3rd fret instead of open G. Next our chord progression turn to G5 and we start to get on flying. Again experiment with chord name tool and make there G major adding one note to G5 shown on first tab. Go ahead and let that B note vibrato a bit :D.

Next part we are goin to A5 part of the riff. Experiment with chord name tool again ^_^. Oh well, we added even one note for it make it scream eh? :D.

And now we are in our last part of our riff and lets do something to get athmosphere up in the crowd and lets take just that note to make it C major and let it scream with vibrato to give us some kicks. But lets take that note little higher octave.

-------------------------------

----------------------5--13~~~~~

--------------4-------5---------

------------5-------------------

----2---5-5---------7-----------

0-0---3---------5-5------------

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of music. It generally derives from observation of how musicians and composers make music, but includes hypothetical speculation. Most commonly, the term describes the academic study and analysis of fundamental elements of music such as pitch, rhythm, harmony, and form, but also refers to descriptions, concepts, or beliefs related to music. Because of the ever-expanding conception of what constitutes music (see Definition of music), a more inclusive definition could be that music theory is the consideration of any sonic phenomena, including silence, as it relates to music.

Music theory is a subfield of musicology, which is itself a subfield within the overarching field of the arts and humanities. Etymologically, music theory is an act of contemplation of music, from the Greek θεωρία, a looking at, viewing, contemplation, speculation, theory, also a sight, a spectacle.[1] As such, it is often concerned with abstract musical aspects such as tuning and tonal systems, scales, consonance and dissonace, and rhythmic relationships, but there is also a body of theory concerning such practical aspects as the creation or the performance of music, orchestration, ornamentation, improvisation, and electronic sound production. A person working in music theory is a music theorist. Methods of analysis include mathematics, graphic analysis, and, especially, analysis enabled by Western music notation. Comparative, descriptive, statistical, and other methods are also used.

The development, preservation, and transmission of music theory may be found in oral and practical music-making traditions, musical instruments, and other artifacts. For example, ancient instruments from Mesopotamia, China, and prehistoric sites around the world reveal details about the music they produced and, potentially, something of the musical theory that might have been used by their makers (see History of music and Musical instrument). In ancient and living cultures around the world, the deep and long roots of music theory are clearly visible in instruments, oral traditions, and current music making. Many cultures, at least as far back as ancient Mesopotamia, Pharoanic Egypt, and ancient China have also considered music theory in more formal ways such as written treatises and music notation.Pitch is the lowness or highness of a tone, for example the difference between middle C and a higher C. The frequency of the sound waves producing a pitch can be measured precisely, but the perception of pitch is more complex because we rarely hear a single frequency or pure pitch. In music, tones, even those sounded by solo instruments or voices, are usually a complex combination of frequencies, and therefore a mix of pitches. Accordingly, theorists often describe pitch as a subjective sensation.

Most people appear to possess relative pitch, which means they perceive each note relative to some reference pitch, or as some interval from the previous pitch. Significantly fewer people demonstrate absolute pitch (or perfect pitch), the ability to identify pitches without comparison to another pitch. Human perception of pitch can be comprehensively fooled to create auditory illusions. Despite these perceptual oddities, perceived pitch is nearly always closely connected with the fundamental frequency of a note, with a lesser connection to sound pressure level, harmonic content (complexity) of the sound, and to the immediately preceding history of notes heard. In general, the higher the frequency of vibration, the higher the perceived pitch. The lower the frequency, the lower the pitch. However, even for tones of equal intensity, perceived pitch and measured frequency do not stand in a simple linear relationship.

Intensity (loudness) can change perception of pitch. Below about 1000 Hz, perceived pitch gets lower as intensity increases. Between 1000 and 2000 Hz, pitch remains fairly constant. Above 2000 Hz, pitch rises with intensity. This is due to the ear's natural sensitivity to higher pitched sound, as well as the ear's particular sensitivity to sound around the 2000–5000 Hz interval, the frequency range most of the human voice occupies.

The difference in frequency between two pitches is called an interval. The most basic interval is the unison, which is simply two notes of the same pitch, followed by the slightly more complex octave: pitches that are either double or half the frequency of the other. The unique characteristics of octaves gave rise to the concept of what is called pitch class, an important aspect of music theory. Pitches of the same letter name that occur in different octaves may be grouped into a single "class" by ignoring the difference in octave. For example, a high C and a low C are members of the same pitch class—the class that contains all C's. The concept of pitch class greatly aids aspects of analysis and composition.

Although pitch can be identified by specific frequency, the letter names assigned to pitches are somewhat arbitrary. For example, today most orchestras assign Concert A (the A above middle C on the piano) to the specific frequency of 440 Hz, rather than, for instance, 435HZ as it was in France in 1859. In England, that A varied between 439 and 452. These differences can have a noticeable effect on the timbre of instruments and other phenomena. Many cultures do not attempt to standardize pitch, often considering that it should be allowed to vary depending on genre, style, mood, etc. In historically informed performance of older music, tuning is often set to match the tuning used in the period when it was written. A frequency of 440 Hz was recommended as the standard pitch for Concert A in 1939, and in 1955 the International Organization for Standardization affirmed the choice. A440 is now widely, though not exclusively, the standard for music around the world.

Pitch is also an important consideration in tuning systems, or temperament, used to determine the intervallic distance between tones, as within a scale. Tuning systems vary widely within and between world cultures. In Western culture, there have long been several competing tuning systems, all with different qualities. Internationally, the system known as equal temperament is most commonly used today because it is considered the most satisfactory compromise that allows instruments of fixed tuning (e.g. the piano) to sound acceptably in tune in all keys.

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of music. It generally derives from observation of how musicians and composers make music, but includes hypothetical speculation. Most commonly, the term describes the academic study and analysis of fundamental elements of music such as pitch, rhythm, harmony, and form, but also refers to descriptions, concepts, or beliefs related to music. Because of the ever-expanding conception of what constitutes music (see Definition of music), a more inclusive definition could be that music theory is the consideration of any sonic phenomena, including silence, as it relates to music.

Music theory is a subfield of musicology, which is itself a subfield within the overarching field of the arts and humanities. Etymologically, music theory is an act of contemplation of music, from the Greek θεωρία, a looking at, viewing, contemplation, speculation, theory, also a sight, a spectacle.[1] As such, it is often concerned with abstract musical aspects such as tuning and tonal systems, scales, consonance and dissonace, and rhythmic relationships, but there is also a body of theory concerning such practical aspects as the creation or the performance of music, orchestration, ornamentation, improvisation, and electronic sound production. A person working in music theory is a music theorist. Methods of analysis include mathematics, graphic analysis, and, especially, analysis enabled by Western music notation. Comparative, descriptive, statistical, and other methods are also used.

The development, preservation, and transmission of music theory may be found in oral and practical music-making traditions, musical instruments, and other artifacts. For example, ancient instruments from Mesopotamia, China, and prehistoric sites around the world reveal details about the music they produced and, potentially, something of the musical theory that might have been used by their makers (see History of music and Musical instrument). In ancient and living cultures around the world, the deep and long roots of music theory are clearly visible in instruments, oral traditions, and current music making. Many cultures, at least as far back as ancient Mesopotamia, Pharoanic Egypt, and ancient China have also considered music theory in more formal ways such as written treatises and music notation.Pitch is the lowness or highness of a tone, for example the difference between middle C and a higher C. The frequency of the sound waves producing a pitch can be measured precisely, but the perception of pitch is more complex because we rarely hear a single frequency or pure pitch. In music, tones, even those sounded by solo instruments or voices, are usually a complex combination of frequencies, and therefore a mix of pitches. Accordingly, theorists often describe pitch as a subjective sensation.

Most people appear to possess relative pitch, which means they perceive each note relative to some reference pitch, or as some interval from the previous pitch. Significantly fewer people demonstrate absolute pitch (or perfect pitch), the ability to identify pitches without comparison to another pitch. Human perception of pitch can be comprehensively fooled to create auditory illusions. Despite these perceptual oddities, perceived pitch is nearly always closely connected with the fundamental frequency of a note, with a lesser connection to sound pressure level, harmonic content (complexity) of the sound, and to the immediately preceding history of notes heard. In general, the higher the frequency of vibration, the higher the perceived pitch. The lower the frequency, the lower the pitch. However, even for tones of equal intensity, perceived pitch and measured frequency do not stand in a simple linear relationship.

Intensity (loudness) can change perception of pitch. Below about 1000 Hz, perceived pitch gets lower as intensity increases. Between 1000 and 2000 Hz, pitch remains fairly constant. Above 2000 Hz, pitch rises with intensity. This is due to the ear's natural sensitivity to higher pitched sound, as well as the ear's particular sensitivity to sound around the 2000–5000 Hz interval, the frequency range most of the human voice occupies.

The difference in frequency between two pitches is called an interval. The most basic interval is the unison, which is simply two notes of the same pitch, followed by the slightly more complex octave: pitches that are either double or half the frequency of the other. The unique characteristics of octaves gave rise to the concept of what is called pitch class, an important aspect of music theory. Pitches of the same letter name that occur in different octaves may be grouped into a single "class" by ignoring the difference in octave. For example, a high C and a low C are members of the same pitch class—the class that contains all C's. The concept of pitch class greatly aids aspects of analysis and composition.

Although pitch can be identified by specific frequency, the letter names assigned to pitches are somewhat arbitrary. For example, today most orchestras assign Concert A (the A above middle C on the piano) to the specific frequency of 440 Hz, rather than, for instance, 435HZ as it was in France in 1859. In England, that A varied between 439 and 452. These differences can have a noticeable effect on the timbre of instruments and other phenomena. Many cultures do not attempt to standardize pitch, often considering that it should be allowed to vary depending on genre, style, mood, etc. In historically informed performance of older music, tuning is often set to match the tuning used in the period when it was written. A frequency of 440 Hz was recommended as the standard pitch for Concert A in 1939, and in 1955 the International Organization for Standardization affirmed the choice. A440 is now widely, though not exclusively, the standard for music around the world.

Pitch is also an important consideration in tuning systems, or temperament, used to determine the intervallic distance between tones, as within a scale. Tuning systems vary widely within and between world cultures. In Western culture, there have long been several competing tuning systems, all with different qualities. Internationally, the system known as equal temperament is most commonly used today because it is considered the most satisfactory compromise that allows instruments of fixed tuning (e.g. the piano) to sound acceptably in tune in all keys.

Harmonic Technique For Guitarist

The Harmonic Minor Scale

Good guitarists have a vast repetoire of harmonic material to draw from. Even in the pop, rock, and blues genres, where pentatonic and blues scales make up the bulk of scales used in improvising, there are times when those scales don't provide the correct color for particular situations. Nor does a 'typical' minor scale, like the natural minor (also known as aeolian). These are times when a guitarist might look to a more exotic sounding scale, like the harmonic minor.

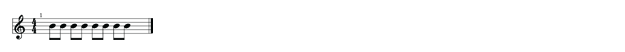

THE NOTES:

The above example illustrates a C harmonic minor scale, constrasted against both the major and natural minor scales. Notice the harmonic minor scale differs from the natural minor scale in just one note; the raised seventh. This note contains the strongest color in the scale, in that it carries a certain degree of tension, and should be used with this knowledge in mind. Hanging onto the seventh degree of the scale, then resolving it up a semi-tone to the root is a nice way to create a tension-release scenario when improvising. The flattened third and sixth note of the harmonic minor scale would generally prevent it from being used against major chords with the same root note in an improvising situation (for example, a C harmonic minor scale would not normally be used against a C major chord).

THE SCALE:

When playing the scale, make sure to do all stretching with the pinky (4th) finger in your left hand. Notes normally played with the pinky should still be played with the pinky (do not stretch with your 3rd finger on the first and sixth strings to play the notes your pinky would normally play - there's no logical reason to do this.) Care should be taken to play the scale accurately and slowly, using alternate picking, until it can be played with reasonable precision. Only then should the scale be attempted at a slightly faster tempo. Using a metronome is, as always, the beneficial way of practising scales such as this.

Root notes of the scale are marked in red, and the last two notes are bracketed to illustrate that the scale is, at this point, extending beyond two octaves.

This illustration is just a jumping-off point for learning the harmonic minor scale. Once comfortable with the sound of the scale, guitarists should teach themselves to play the scale all over the fretboard in different positions, up one string, etc. either by using their ear to figure out the correct notes, or by following the scale steps illustrated above and below.

DIATONIC CHORDS OF:

Like the major scale, we can derive a series of chords out of each of the seven notes in the harmonic minor scale, by stacking each note with notes from the scale a diatonic third and fifth above it. Although the end process may not yield a set of chords as user-friendly as those derived from the major scale, they are nonetheless important to know and understand. Using the above illustration, for example, we can see if a progression moves from Vmaj to Imin, the harmonic minor scale would be an appropriate choice.

The harmonic minor scale can also be "forced" over a static chord progression that does not initially seem receptive to the harmonic minor sound. For example, a tune in the key of A minor, that vamps on Amin for a long time, can often be a good situation to use the harmonic minor scale. It will often create a sound that could be considered exotic, or unusual, so be prepared for this.

The harmonic minor is just one of many scales that can be used to provide different color to minor chords (others include melodic minor, phrygian, dorian, etc.) For every minute spent practising the scale itself, guitarists should spend another minute listening to each note of the scale against a repeatedly strummed minor chord (record a rhythm track of yourself playing), paying attention to the specific color each note gives, and where it wants to resolve to. Also, listen for the use of the harmonic minor scale by your favorite guitarist. Be able to sing the scale without having to think about it. Practise moving from a minor pentatonic into a harmonic minor scale, and back again. Learning a scale goes far beyond memorizing the shape on the neck of the guitar; it involves internalizing the sound of the scale itself.

Saturday, April 11, 2015

Intermediate 12-Bar Blues Riff

This riff has the same structure as the basic 12-bar blues riff we’ve already learned, but we’re going to add a few extra notes and some motion to it to make it a little more interesting. Since we’re still working with the standard 12-bar blues progression, you should know the first four bars are over an E chord.

Last time we started with an two-note E power chord, but now we’ll use a three-note version. Place your first finger on the second fret of the A string and D string, and strum the sixth, fifth, and fourth strings twice. These will be your first two swung eighth notes. Remember to use the muting technique from the last lesson.

Keeping your first finger in place, place your third finger on the fourth fret of the A string and play two more swung eighth notes. Now leave those two fingers there, place your fourth finger on the fifth fret of the A string, and play two more swung eighth notes.

Now take your fourth finger off, leaving your other fingers in place, and play another two swung eighth notes. This makes up the foundation riff to play over your E chord, and it finishes your first whole measure.

You’ll start measure two the same exact way until you get to beat three, where you need to play a regular E power chord. On the “and” of beat three we have a small tag riff, so keep your first finger in place for the B note on the second fret of the A string and play it with an upstroke. Move your second finger to the third fret of the low E string with a downstroke. Next hammer on the low E string with your third finger on the fourth fret. To finish this tag riff, go back to the B note with your first finger on the second fret of the A string with an upstroke. In the video you can see me play with tag riff with an upstroke, downstroke, hammer-on, and then an upstroke.

This basic riff with the tag takes up the first two measures of the 12-bar blues progression. Since we have four measures of the 1 chord we need to play this riff twice. Playing this riff twice takes care of the first four measures of E in the standard 12-bar blues riff. In the video, you can see what we’ve learned so far as I play those first four measures.

When we get to measure five, we switch to our 4 chord, which is an A. We’re going to use the same idea, but it will be a bit different. Start with an open A chord on the second fret, but use your first finger to cover the D, G, and B strings. Strum the inside four strings, leaving both E strings out, for two swung eighth notes.

For the second measure of the A chord, you’re going to start the same way. Two swung eighth notes for the A, then put your second and third fingers down again for two eighth notes. On beat three you need to go back to just the A for one eighth note. From here, you’ll play that same tag riff again to finish off this second measure of A. This is a lot of information so far in this 12-bar blues riff, so take some time to get this under your fingers.

Next comes the 5 chord, and I kept this part of the 12-bar blues riff the same as the basic version we learned in the last lesson. Go to a B power chord for one measure and play the regular riff. Now we’re back to the 4 chord, so make an A chord shape again and play the first measure of the A chord riff from earlier.

We have one measure of the 1 chord next, so play just the first measure of the 1 chord riff again. To end the riff, we’re going to finish with the 5 chord, which is the B power chord again. Play just up to beat three of the riff over the B chord, and then play the tag riff to finish the “and 4 and” of the measure and the end this intermediate 12-bar blues riff.

Now that you’ve learned the entire thing, you can watch me play the whole riff along with the jam track. This riff is just an example of what you do when you get creative with the basic blues rhythm riff we learned in the last lesson. Once you have this down, you can take some time to experiment with it yourself. See if you can change a few notes or rhythms up and come up with your own version of the riff.

There are two main types of acoustic guitar namely steel-string acoustic guitars and classical guitars. Steel-string acoustic guitars produce a metallic sound that is a distinctive component of a wide range of popular genres. Steel-string acoustic guitars are sometimes referred to as flat tops. The word top refers to the face or front of the guitar which is called the table. Classical guitars have a wide neck and use nylon strings. They are primarily associated with the playing of the solo classical guitar repertoire. Classical guitars are sometimes referred to as spanish guitars in recognition of their country of origin.

The acoustic guitar lends itself to a variety of tasks and roles. Its portability and ease of use make it the ideal songwriter's tool. Its gentle harp-like arpeggios and rhythmic chordal strumming has always found favor in an ensemble. The acoustic guitar has a personal and intimate quality that is suited to small halls, churches and private spaces. For larger venues some form of amplification is required. An acoustic guitar can be amplified by placing a microphone in front of the sound hole or by installing a pickup. There are many entry-level acoustic guitar models that are manufactured to a high standard and these are entirely suitable as a first guitar for beginners.Electric guitars are solid-bodied guitars that are designed to be plugged into an amplifier. The electric guitar when amplified produces a sound that is metallic with a lengthy decay. The shape of the electric guitar is not determined by the need for a deep resonating body and this had led to the development of contoured and thin bodied electric guitars. The two most popular designs are the Fender Stratocaster and the Gibson Les Paul.

Electric guitar strings are thinner than acoustic guitar strings and closer to the neck and therefore less force is needed to press them down. The ease with which you can bend strings, clear access to the twelfth position, the use of a whammy bar and the manipulation of pots and switches whilst playing has led to the development of a lead guitar style that is unique to the instrument. Fret-tapping is a guitar technique for creating chords and melody lines that are not possible using the standard technique of left-hand fretting and right-hand strumming. The sustain, sensitive pick-ups, low action and thin strings of the electric guitar make it an ideal instrument for fret-tapping.Electro-acoustic guitars have pickups that are specifically designed to reproduce the subtle nuances of the acoustic guitar timbre. Electro-acoustic pickups are designed to sound neutral with little alteration to the acoustic tone. The Ovation range of electro-acoustic guitars have under-the-saddle piezo pickups and a synthetic bowl-back design. The synthetic bowl-back ensures a tough construction that stands up to the rigours of the road while offering less feedback at high volumes. Ovation were the first company to provide on-board equalization and this is now a standard feature. The Taylor electro-acoustic range uses the traditional all-wood construction and the necks of these guitars have a reputation for superb action and playability. Yamaha, Maton and many other companies manufacture electro-acoustic guitars and the buyer is advised to test as many models and makes as they can while taking note of the unplugged and amplified sound.The twelve-string guitar is a simple variation of the normal six string design. Twelve-string guitars have six regular strings and a second set of thinner strings. Each string of the second set corresponds to the note of its regular string counterpart. The strings form pairs and therefore you play a twelve-string guitar in the same manner as you would a standard six-string.

Twelve-string guitars produce a brighter and more jangly tone than six-string guitars. They are used by guitarists for chord progressions that require thickening. The twelve-string is mainly used as a rhythm instrument due to the extra effort involved in playing lead guitar using paired strings. Twelve-string guitars have twelve tuning pegs and double truss rods and are slightly more expensive then their corresponding six-string version.The steel guitar is unusual in that it is played horizontally across the player's lap. The steel guitar originates from Hawaii where local musicians, newly introduced to the European guitar, developed a style of playing involving alternative tunings and the use of a slide. The Hawaiian guitarists found that by laying the guitar flat across the lap they could better control the slide. In response to this new playing style some Hawaiian steel guitars were constructed with a small rectangular body which made them more suitable for laying across the lap.

There are two types of steel guitar played with a steel, the solid metal bar from which the guitar takes its name, namely the lap steel guitar and the pedal steel guitar with its extra necks. The pedal steel guitar comes on its own stand with a mechanical approach similar to the harp. Pedals and knee-levers are used to alter the pitch of the strings whilst playing thereby extending the fluency of the glissandi technique.

The acoustic guitar lends itself to a variety of tasks and roles. Its portability and ease of use make it the ideal songwriter's tool. Its gentle harp-like arpeggios and rhythmic chordal strumming has always found favor in an ensemble. The acoustic guitar has a personal and intimate quality that is suited to small halls, churches and private spaces. For larger venues some form of amplification is required. An acoustic guitar can be amplified by placing a microphone in front of the sound hole or by installing a pickup. There are many entry-level acoustic guitar models that are manufactured to a high standard and these are entirely suitable as a first guitar for beginners.Electric guitars are solid-bodied guitars that are designed to be plugged into an amplifier. The electric guitar when amplified produces a sound that is metallic with a lengthy decay. The shape of the electric guitar is not determined by the need for a deep resonating body and this had led to the development of contoured and thin bodied electric guitars. The two most popular designs are the Fender Stratocaster and the Gibson Les Paul.

Electric guitar strings are thinner than acoustic guitar strings and closer to the neck and therefore less force is needed to press them down. The ease with which you can bend strings, clear access to the twelfth position, the use of a whammy bar and the manipulation of pots and switches whilst playing has led to the development of a lead guitar style that is unique to the instrument. Fret-tapping is a guitar technique for creating chords and melody lines that are not possible using the standard technique of left-hand fretting and right-hand strumming. The sustain, sensitive pick-ups, low action and thin strings of the electric guitar make it an ideal instrument for fret-tapping.Electro-acoustic guitars have pickups that are specifically designed to reproduce the subtle nuances of the acoustic guitar timbre. Electro-acoustic pickups are designed to sound neutral with little alteration to the acoustic tone. The Ovation range of electro-acoustic guitars have under-the-saddle piezo pickups and a synthetic bowl-back design. The synthetic bowl-back ensures a tough construction that stands up to the rigours of the road while offering less feedback at high volumes. Ovation were the first company to provide on-board equalization and this is now a standard feature. The Taylor electro-acoustic range uses the traditional all-wood construction and the necks of these guitars have a reputation for superb action and playability. Yamaha, Maton and many other companies manufacture electro-acoustic guitars and the buyer is advised to test as many models and makes as they can while taking note of the unplugged and amplified sound.The twelve-string guitar is a simple variation of the normal six string design. Twelve-string guitars have six regular strings and a second set of thinner strings. Each string of the second set corresponds to the note of its regular string counterpart. The strings form pairs and therefore you play a twelve-string guitar in the same manner as you would a standard six-string.

Twelve-string guitars produce a brighter and more jangly tone than six-string guitars. They are used by guitarists for chord progressions that require thickening. The twelve-string is mainly used as a rhythm instrument due to the extra effort involved in playing lead guitar using paired strings. Twelve-string guitars have twelve tuning pegs and double truss rods and are slightly more expensive then their corresponding six-string version.The steel guitar is unusual in that it is played horizontally across the player's lap. The steel guitar originates from Hawaii where local musicians, newly introduced to the European guitar, developed a style of playing involving alternative tunings and the use of a slide. The Hawaiian guitarists found that by laying the guitar flat across the lap they could better control the slide. In response to this new playing style some Hawaiian steel guitars were constructed with a small rectangular body which made them more suitable for laying across the lap.

There are two types of steel guitar played with a steel, the solid metal bar from which the guitar takes its name, namely the lap steel guitar and the pedal steel guitar with its extra necks. The pedal steel guitar comes on its own stand with a mechanical approach similar to the harp. Pedals and knee-levers are used to alter the pitch of the strings whilst playing thereby extending the fluency of the glissandi technique.

Basic 12-Bar Blues Riff

For this basic blues riff, there is quite a bit of stretching involved, so don’t feel bad if you don’t get the hang of it right away. It will take some work to get comfortable with stretching that far. What we’re going to do is outline the chords throughout the 12-bar blues progression with this riff, and apply a shuffle rhythm. We’re also going to use a muting technique to give your playing a more bluesy style.

Let’s jump right into this riff. In our 12-bar blues progression, the first four measures are over the 1 chord, so we’ll learn the riff that goes over this chord. Start with an E power chord and play that twice with two eighth notes, using a swing feel. Next, leaving your index finger where it is, place your third finger on the fourth fret of the A string and play that twice using two swung eighth notes. This is basically the entire riff, you’re just going to repeat it over again.

This has taken up only two beats so far, so to get a whole measure, we need to play this riff twice. Since we have four measures of the 1 chord, we’ll need to play this short riff eight times in a row.

The 12-bar blues progression switches to the 4 chord for two measures next. For this riff, we’ll make an A power chord by placing your index finger on the second fret of the D string, and play the fifth and fourth strings twice using two swing eighth notes. Keeping your index finger in place, come down with your third finger on the fourth fret of the D string, and play that twice using two swung eighth notes. This will be your basic riff over the A chord.

Now here comes the stretching part that I mentioned earlier. When you go to the 5 chord, which is a B, we’re going to have to make a B power chord. Because of the stretch in it, we have to make it with our first and second fingers rather than first and third fingers. Place your first finger on the second fret of the A string and your second finger on the fourth fret of the D string. Play this for two swung eighth notes. Now you have to stretch your fourth finger all the way to sixth fret and play the A and D strings for two swung eighth notes. This may take you a while to get that stretch down.

Now we have a measure of the 4 chord, so head back to your A riff and play it for one measure. After that, go back to the 1 chord for one measure. Finally we end of the 5 chord for one measure, so make the B power chord shape again and stretch your pinky out to play that B riff for one measure.

Now that we’ve walked through this riff, take a look at the video to hear what it will sound like with the jam track. This is the basic 12-bar blues riff we’re going to learn altogether in the context of some real music.

Now that you’ve learned this simple 12-bar blues riff, you can really hear how it livens up your rhythm blues playing and gives it some forward momentum. This is the most basic version of this rhythm riff that we’ll learn, and it’s important to get it down because it’s the foundation of another version of the riff we’ll learn later.

Slow this riff down and practice it as much as you need to until you feel really comfortable with it, then you can pull up a jam track. Try playing along to either the 70 beats per minute or the 100 beats per minute jam track.

The guitar is an ancient and noble instrument, whose history can be traced back over 4000 years. Many theories have been advanced about the instrument's ancestry. It has often been claimed that the guitar is a development of the lute, or even of the ancient Greek kithara. Research done by Dr. Michael Kasha in the 1960's showed these claims to be without merit. He showed that the lute is a result of a separate line of development, sharing common ancestors with the guitar, but having had no influence on its evolution. The influence in the opposite direction is undeniable, however - the guitar's immediate forefathers were a major influence on the development of the fretted lute from the fretless oud which the Moors brought with them to to Spain.

The sole "evidence" for the kithara theory is the similarity between the greek word "kithara" and the Spanish word "quitarra". It is hard to imagine how the guitar could have evolved from the kithara, which was a completely different type of instrument - namely a square-framed lap harp, or "lyre".

It would also be passing strange if a square-framed seven-string lap harp had given its name to the early Spanish 4-string "quitarra". Dr. Kasha turns the question around and asks where the Greeks got the name "kithara", and points out that the earliest Greek kitharas had only 4 strings when they were introduced from abroad. He surmises that the Greeks hellenified the old Persian name for a 4-stringed instrument, "chartar". The earliest stringed instruments known to archaeologists are bowl harps and tanburs. Since prehistory people have made bowl harps using tortoise shells and calabashes as resonators, with a bent stick for a neck and one or more gut or silk strings. The world's museums contain many such "harps" from the ancient Sumerian, Babylonian, and Egyptian civilisations. Around 2500 - 2000 CE more advanced harps, such as the opulently carved 11-stringed instrument with gold decoration found in Queen Shub-Ad's tomb, started to appear.A tanbur is defined as "a long-necked stringed instrument with a small egg- or pear-shaped body, with an arched or round back, usually with a soundboard of wood or hide, and a long, straight neck". The tanbur probably developed from the bowl harp as the neck was straightened out to allow the string/s to be pressed down to create more notes. Tomb paintings and stone carvings in Egypt testify to the fact that harps and tanburs (together with flutes and percussion instruments) were being played in ensemble 3500 - 4000 years ago.At around the same time that Torres started making his breakthrough fan-braced guitars in Spain, German immigrants to the USA - among them Christian Fredrich Martin - had begun making guitars with X-braced tops. Steel strings first became widely available in around 1900. Steel strings offered the promise of much louder guitars, but the increased tension was too much for the Torres-style fan-braced top. A beefed-up X-brace proved equal to the job, and quickly became the industry standard for the flat-top steel string guitar.

At the end of the 19th century Orville Gibson was building archtop guitars with oval sound holes. He married the steel-string guitar with a body constructed more like a cello, where the bridge exerts no torque on the top, only pressure straight down. This allows the top to vibrate more freely, and thus produce more volume. In the early 1920's designer Lloyd Loar joined Gibson, and refined the archtop "jazz" guitar into its now familiar form with f-holes, floating bridge and cello-type tailpiece.

The electric guitar was born when pickups were added to Hawaiian and "jazz" guitars in the late 1920's, but met with little success before 1936, when Gibson introduced the ES150 model, which Charlie Christian made famous.

With the advent of amplification it became possible to do away with the soundbox altogether. In the late 1930's and early 1940's several actors were experimenting along these lines, and controversy still exists as to whether Les Paul, Leo Fender, Paul Bigsby or O.W. Appleton constructed the very first solid-body guitar. Be that as it may, the solid-body electric guitar was here to stay.

The guitar is an ancient and noble instrument, whose history can be traced back over 4000 years. Many theories have been advanced about the instrument's ancestry. It has often been claimed that the guitar is a development of the lute, or even of the ancient Greek kithara. Research done by Dr. Michael Kasha in the 1960's showed these claims to be without merit. He showed that the lute is a result of a separate line of development, sharing common ancestors with the guitar, but having had no influence on its evolution. The influence in the opposite direction is undeniable, however - the guitar's immediate forefathers were a major influence on the development of the fretted lute from the fretless oud which the Moors brought with them to to Spain.

The sole "evidence" for the kithara theory is the similarity between the greek word "kithara" and the Spanish word "quitarra". It is hard to imagine how the guitar could have evolved from the kithara, which was a completely different type of instrument - namely a square-framed lap harp, or "lyre".

It would also be passing strange if a square-framed seven-string lap harp had given its name to the early Spanish 4-string "quitarra". Dr. Kasha turns the question around and asks where the Greeks got the name "kithara", and points out that the earliest Greek kitharas had only 4 strings when they were introduced from abroad. He surmises that the Greeks hellenified the old Persian name for a 4-stringed instrument, "chartar". The earliest stringed instruments known to archaeologists are bowl harps and tanburs. Since prehistory people have made bowl harps using tortoise shells and calabashes as resonators, with a bent stick for a neck and one or more gut or silk strings. The world's museums contain many such "harps" from the ancient Sumerian, Babylonian, and Egyptian civilisations. Around 2500 - 2000 CE more advanced harps, such as the opulently carved 11-stringed instrument with gold decoration found in Queen Shub-Ad's tomb, started to appear.A tanbur is defined as "a long-necked stringed instrument with a small egg- or pear-shaped body, with an arched or round back, usually with a soundboard of wood or hide, and a long, straight neck". The tanbur probably developed from the bowl harp as the neck was straightened out to allow the string/s to be pressed down to create more notes. Tomb paintings and stone carvings in Egypt testify to the fact that harps and tanburs (together with flutes and percussion instruments) were being played in ensemble 3500 - 4000 years ago.At around the same time that Torres started making his breakthrough fan-braced guitars in Spain, German immigrants to the USA - among them Christian Fredrich Martin - had begun making guitars with X-braced tops. Steel strings first became widely available in around 1900. Steel strings offered the promise of much louder guitars, but the increased tension was too much for the Torres-style fan-braced top. A beefed-up X-brace proved equal to the job, and quickly became the industry standard for the flat-top steel string guitar.

At the end of the 19th century Orville Gibson was building archtop guitars with oval sound holes. He married the steel-string guitar with a body constructed more like a cello, where the bridge exerts no torque on the top, only pressure straight down. This allows the top to vibrate more freely, and thus produce more volume. In the early 1920's designer Lloyd Loar joined Gibson, and refined the archtop "jazz" guitar into its now familiar form with f-holes, floating bridge and cello-type tailpiece.

The electric guitar was born when pickups were added to Hawaiian and "jazz" guitars in the late 1920's, but met with little success before 1936, when Gibson introduced the ES150 model, which Charlie Christian made famous.

With the advent of amplification it became possible to do away with the soundbox altogether. In the late 1930's and early 1940's several actors were experimenting along these lines, and controversy still exists as to whether Les Paul, Leo Fender, Paul Bigsby or O.W. Appleton constructed the very first solid-body guitar. Be that as it may, the solid-body electric guitar was here to stay.

Playing Your First Solo Song

For your solo, we’ll be using the major scale, the major pentatonic scale, and the minor pentatonic scale, but we’ll be moving the minor pentatonic scale shape from a G minor pentatonic up the fretboard to an E minor pentatonic scale shape. You may want to spend some time practicing the scale in this new position before continuing.

I’ve got a new jam track for you to play this solo with, and it’s 24 bars long. The first 16 bars are over a G major chord, then two bars of E minor, two bars of G major, two bars of E minor, and you’ll finish off bar 23 and 24 on a G major. Listen to this jam track a few times to get a feel for the music. The 24 bars are repeated four times so it’s easy to practice the solo over and over.

I’ll break this solo down one phrase at a time, so you can learn step by step. The first lick starts with a major scale, so place your third finger on the fourth fret of the G string and bend that note. Come back to the second fret, and then place your fourth finger on the fifth fret of the D string. Use the roll technique to move your pinky up to the A string, hold it for six beats, and then rest. That’s the first lick of your solo, and it’s the repeating theme that I mentioned in the last lesson.

The next phrase starts with the same bend again on the G string, and moves to the fifth fret. Move to the third fret of the B string with your second finger, hit the same note again for six beats, and rest. This second lick, paired with the first lick, makes up the first sentence of the solo.

The second sentence starts with the repeating theme, so play the first lick of the solo again. After that, the next phrase starts out the same, but will end with a quick pentatonic run. Bend the fourth fret of the G string again, but from there, hit the second fret of the D string with your first finger, then the fourth fret with your third finger. Move to the B string, grabbing the third fret with your second finger, the fifth fret with your pinky, and end with the G root note on the third fret of the high E string with your second finger. That wraps up this phrase and the second sentence of the solo.

Remember that when you’re holding a note for a few beats you should add some vibrato to give the note more expression. Feel free to pause wherever you like to practice sections of the solo together before moving on.

Up to this point in the jam track, we’ve been playing to a G major chord, and that’s why we’ve been playing G major scales. The next two measures switch to an E minor chord, so we’ll switch to an E minor pentatonic scale that way our solo fits the music we’re playing to. Remember though that we’re moving this scale shape up the fretboard to the 12th fret of the low E string.

This next lick is an E minor pentatonic scale, and we’re going to play through this scale. Pick the first note of the scale, hammer-on to the 15th fret, pick the 13th fret of the A string, hammer-on to the 15th fret, pick the 13th fret of the D string, and hammer-on to the 15th fret. Finish off this lick by picking the 12th fret of the G string and the E root note on the 14th note of the D string. That’s measure 17 and 18, the first whole phrase of this sentence.

Now we have two measures of a G chord to play over, so we’re going to come down on the 12th fret of the G string, which is the G root note. You’ll play this note for a full bar, and again for another full bar, which is measures 19 and 20.

Measures 21 and 22 are back on the E minor chord, so we’ll start playing with our E minor pentatonic scale again. We’re going to repeat the first E minor lick we played, but go an octave higher by starting on the 14th fret this time. Walk up the pentatonic scale, and when you get to the highest note, come back to the root note on the 14th fret of the high E string.

Measures 23 and 24 are played over the G major chord again, so we’ll go back to a G major scale, starting an octave higher on the 15th fret. Put your pinky on the 17th fret of the high E string, bend it up a whole step, and then play the G root note on the 15th fret with your middle finger. That’s going to finish the last sentence, and wrap up your solo.

Once you’ve learned this solo, pull up the jam track so you can play your solo over music. After that, you can experiment using different scales along with the jam track to make up your own solos. Just be sure to match up your scale with the key that’s being played on the jam track.

Playing A Guitar Solo

In this lesson, I’m going to give you some tips for building your own guitar solos. These tips will help you create solos that sound like more than just playing up and down basic scales. We’re going to cover concepts such as phrasing, repeating themes, leaving space, building your solos dynamically, and playing over simple chord changes.

If you’re joining this series for the first time, I definitely recommend going back to the first lesson and working through all the videos in the Lead Guitar Quick-Start Series because a lot of the foundational skills we’re using are covered throughout those lessons.

The first concept I want to talk about is phrasing, because it’s good to structure your solo like you’re having a conversation with someone. If I’m talking to someone, I don’t run all my sentences together in a monotonous tone because that wouldn’t make much sense and wouldn’t be very interesting. That would be the same as playing a guitar solo that just runs up and down a scale.

When you’re talking to someone, you leave pauses, have inflections in your voice, and have rest times where you wait for a moment. Sometimes you want your guitar solos to be the same way. Your solo can be more interesting if you pause here and there and build inflections in your playing.

The next idea I want to talk to you about is having a repeating theme in your solo. You won’t always have a repeating theme in your solo, but it’s nice to have a recurring theme in your solo. The theme will help tie everything in your solo together, giving it a cohesive feel. Repeating a theme will also help you with your phrasing because it leaves natural pauses in your solo. In the next lesson you’ll see a great example because there’s an obvious repeating theme in the solo I’ve written for you.

Something that’s hard for guitarists is to leave space between notes, because we’re used to practicing scales and we naturally want to play through them quickly. Be sure to sometimes leave some space in your solos to keep your audience engaged and keep them dialed in to your music. In the solo you’ll be learning, you’ll play the recurring theme, leave a space, and then play the theme again.

Building your solos dynamically is another way to make your solos interesting and keep your listeners engaged. That could mean you start your solo quietly, slowly build it up, and then by the end, it’s natural to end off with a faster lick or a higher volume.

This won’t be the case with every solo you play, but keeping dynamics in mind is a great tool to pull out, especially if you’re playing a song that is emotional or you want to end off with a crescendo. If you think about it like an action movie, there are still down times during the movie so that the action really stands out.

The next tip I have for you is to start playing over chord changes, meaning you should be changing the notes you play in your solo to fit with the chords that are happening in your song. In the next lesson, the two chords we have in the jam track for your solo are G major and E minor, so we’ll adjust our notes according to those chords. When the G major chord is playing, we’ll use G major and G major pentatonic scales. When the E minor is playing, we’ll switch to an E minor pentatonic scale to match. That’s going to be an easy example to begin with, so it’s perfect for starting to think about notes you’re going to play rather than just playing up and down one scale.

Those are a few general, useful tips for building your solo that will come in handy throughout the next lesson, and the rest of your guitar-playing career. Of course, you won’t use these tips in every solo you play, but they’re really helpful for making your solos sound more musical, and not like you’re just practicing scales.

Hammer-Ons & Pull-Offs

You don’t want to come down or hammer-on the string too hard, otherwise the note will go sharp. You also don’t want to hammer-on too softly otherwise the note may come out too quietly. Try to hammer-on just right so the note comes out at the same volume as the picked note, and watch to make sure you’re hammering-on right behind the fret. Practice this first half of the legato technique to get comfortable with it.

The second half of the legato technique is pull-offs. Put your first finger on the third fret of the D string again, but put your third finger on the fifth fret at the same time. Pick the D string so the note from the fifth fret rings out, and then pull-off that note using your third finger to lightly pluck the string with your fretting hand.

Just like the hammer-ons, be careful to pull-off just right. If you pull-off too hard, the note will go out of tune, and if you pull-off too softly, the note may not play at all. Keep a good balance so the note you pick and the note you pull-off have the same volume.

Go ahead with practicing these techniques. It’s okay if it takes weeks or even months to master hammer-ons and pull-offs, because it does take a while to develop these techniques.

Now let’s combine hammer-ons and pull-offs for the full legato technique. Head back to the same two frets we were playing. First finger on the third fret of the D string, pick that note, hammer-on to the fifth fret with your third finger, and right after you hammer-on, pull-off the note. So that’s a quick pick, hammer-on, and pull-off in a row, and once you have that down, you can keep alternating hammer-ons and pull-offs without needing to pick another note.

You now know the core of the legato technique. Being able to hammer-on and pull-off well saves your picking hand some work, and sounds much smoother as you play. Next, we’ll apply the legato technique to the minor pentatonic scale. If you’re just jumping in the Lead Guitar Quick-Start series here, I’d suggest heading back to the video where we learn the minor pentatonic scale.

When using the legato technique with scales, the aim is to use hammer-ons whenever you’re ascending the scale, and use pull-offs when you’re descending the scale. Looking at the minor pentatonic scale, you pick the first note of the scale and then hammer-on to the second. Because this scale has two notes on every string, you’ll always pick the first note and hammer-on to the second note. When you compare my playing in the video, using legato sounds much smoother than picking every single note.

Trying to play the minor pentatonic scale using legato may be difficult for you because it is a tough workout for your pinky, especially if you don’t have a lot of strength built up yet. Just keep working on it and your fingers will get stronger every time you practice.

Now let’s try descending back through this scale. On the high E string, you’ll need to have both your pinky and index finger on the string. Pick the first note with your pick and then pull-off to the second note. When pulling-off, there are a couple of thoughts on how to do this. You can continue to have both fingers planted on the string as you just did, or you can pick your first note and come down on the next note with your other finger quickly afterwards. Either way is acceptable, so try both and see which works best for you.

Work on the legato technique by practicing ascending and descending through the scale, and keep in mind, you don’t have to go all the through the scale before starting again. Feel free to mix it up by going up a few notes and back down a few. You should feel like you have a new tool to add to your playing skills, so work on this with the three scales you know so far – the major scale, major pentatonic scale, and the minor pentatonic scale.

The major scale will be more difficult than the others because the major scale has more notes, and some of the strings have two notes while other strings have three. Starting with the low E string, you’ll pick the first note and hammer-on the second note. With three notes on the A string, you’ll first pick, then hammer-on the second note, and hammer-on again for the third note. Keep that going all the way up the scale. When you’re coming back down the scale, the high E string will start with a pick, followed by two pull-offs.

The guitar is an ancient and noble instrument, whose history can be traced back over 4000 years. Many theories have been advanced about the instrument's ancestry. It has often been claimed that the guitar is a development of the lute, or even of the ancient Greek kithara. Research done by Dr. Michael Kasha in the 1960's showed these claims to be without merit. He showed that the lute is a result of a separate line of development, sharing common ancestors with the guitar, but having had no influence on its evolution. The influence in the opposite direction is undeniable, however - the guitar's immediate forefathers were a major influence on the development of the fretted lute from the fretless oud which the Moors brought with them to to Spain.

The sole "evidence" for the kithara theory is the similarity between the greek word "kithara" and the Spanish word "quitarra". It is hard to imagine how the guitar could have evolved from the kithara, which was a completely different type of instrument - namely a square-framed lap harp, or "lyre".

It would also be passing strange if a square-framed seven-string lap harp had given its name to the early Spanish 4-string "quitarra". Dr. Kasha turns the question around and asks where the Greeks got the name "kithara", and points out that the earliest Greek kitharas had only 4 strings when they were introduced from abroad. He surmises that the Greeks hellenified the old Persian name for a 4-stringed instrument, "chartar". The earliest stringed instruments known to archaeologists are bowl harps and tanburs. Since prehistory people have made bowl harps using tortoise shells and calabashes as resonators, with a bent stick for a neck and one or more gut or silk strings. The world's museums contain many such "harps" from the ancient Sumerian, Babylonian, and Egyptian civilisations. Around 2500 - 2000 CE more advanced harps, such as the opulently carved 11-stringed instrument with gold decoration found in Queen Shub-Ad's tomb, started to appear.A tanbur is defined as "a long-necked stringed instrument with a small egg- or pear-shaped body, with an arched or round back, usually with a soundboard of wood or hide, and a long, straight neck". The tanbur probably developed from the bowl harp as the neck was straightened out to allow the string/s to be pressed down to create more notes. Tomb paintings and stone carvings in Egypt testify to the fact that harps and tanburs (together with flutes and percussion instruments) were being played in ensemble 3500 - 4000 years ago.At around the same time that Torres started making his breakthrough fan-braced guitars in Spain, German immigrants to the USA - among them Christian Fredrich Martin - had begun making guitars with X-braced tops. Steel strings first became widely available in around 1900. Steel strings offered the promise of much louder guitars, but the increased tension was too much for the Torres-style fan-braced top. A beefed-up X-brace proved equal to the job, and quickly became the industry standard for the flat-top steel string guitar.

At the end of the 19th century Orville Gibson was building archtop guitars with oval sound holes. He married the steel-string guitar with a body constructed more like a cello, where the bridge exerts no torque on the top, only pressure straight down. This allows the top to vibrate more freely, and thus produce more volume. In the early 1920's designer Lloyd Loar joined Gibson, and refined the archtop "jazz" guitar into its now familiar form with f-holes, floating bridge and cello-type tailpiece.

The electric guitar was born when pickups were added to Hawaiian and "jazz" guitars in the late 1920's, but met with little success before 1936, when Gibson introduced the ES150 model, which Charlie Christian made famous.

With the advent of amplification it became possible to do away with the soundbox altogether. In the late 1930's and early 1940's several actors were experimenting along these lines, and controversy still exists as to whether Les Paul, Leo Fender, Paul Bigsby or O.W. Appleton constructed the very first solid-body guitar. Be that as it may, the solid-body electric guitar was here to stay.

The sole "evidence" for the kithara theory is the similarity between the greek word "kithara" and the Spanish word "quitarra". It is hard to imagine how the guitar could have evolved from the kithara, which was a completely different type of instrument - namely a square-framed lap harp, or "lyre".

It would also be passing strange if a square-framed seven-string lap harp had given its name to the early Spanish 4-string "quitarra". Dr. Kasha turns the question around and asks where the Greeks got the name "kithara", and points out that the earliest Greek kitharas had only 4 strings when they were introduced from abroad. He surmises that the Greeks hellenified the old Persian name for a 4-stringed instrument, "chartar". The earliest stringed instruments known to archaeologists are bowl harps and tanburs. Since prehistory people have made bowl harps using tortoise shells and calabashes as resonators, with a bent stick for a neck and one or more gut or silk strings. The world's museums contain many such "harps" from the ancient Sumerian, Babylonian, and Egyptian civilisations. Around 2500 - 2000 CE more advanced harps, such as the opulently carved 11-stringed instrument with gold decoration found in Queen Shub-Ad's tomb, started to appear.A tanbur is defined as "a long-necked stringed instrument with a small egg- or pear-shaped body, with an arched or round back, usually with a soundboard of wood or hide, and a long, straight neck". The tanbur probably developed from the bowl harp as the neck was straightened out to allow the string/s to be pressed down to create more notes. Tomb paintings and stone carvings in Egypt testify to the fact that harps and tanburs (together with flutes and percussion instruments) were being played in ensemble 3500 - 4000 years ago.At around the same time that Torres started making his breakthrough fan-braced guitars in Spain, German immigrants to the USA - among them Christian Fredrich Martin - had begun making guitars with X-braced tops. Steel strings first became widely available in around 1900. Steel strings offered the promise of much louder guitars, but the increased tension was too much for the Torres-style fan-braced top. A beefed-up X-brace proved equal to the job, and quickly became the industry standard for the flat-top steel string guitar.

At the end of the 19th century Orville Gibson was building archtop guitars with oval sound holes. He married the steel-string guitar with a body constructed more like a cello, where the bridge exerts no torque on the top, only pressure straight down. This allows the top to vibrate more freely, and thus produce more volume. In the early 1920's designer Lloyd Loar joined Gibson, and refined the archtop "jazz" guitar into its now familiar form with f-holes, floating bridge and cello-type tailpiece.

The electric guitar was born when pickups were added to Hawaiian and "jazz" guitars in the late 1920's, but met with little success before 1936, when Gibson introduced the ES150 model, which Charlie Christian made famous.

With the advent of amplification it became possible to do away with the soundbox altogether. In the late 1930's and early 1940's several actors were experimenting along these lines, and controversy still exists as to whether Les Paul, Leo Fender, Paul Bigsby or O.W. Appleton constructed the very first solid-body guitar. Be that as it may, the solid-body electric guitar was here to stay.

Develop your Timing And Feel

In this lesson, we’re going to continue to focus on your strumming by developing your timing and feel. This is a critical area of musicianship that is important for you to develop. If you have good timing, people will enjoy listening to you and they’ll enjoy playing along with you. If your timing isn’t good, people won’t enjoy listening to you as much and they’ll be frustrated if they play with you too.

One of the key elements to developing your timing is practicing with a metronome. You can use the jam tracks I have supplied here as well, but it’s important to have a constant beat to help keep you on track. Sometimes guitar players don’t realize they have timing problems until they get into a situation where it’s really obvious and embarrassing for them. Don’t let that be you! Work on your timing and really get it down.

I’m going to teach you a great exercise for developing your timing and feel, and you need to be familiar with note subdivisions to play through the exercise. The subdivisions I’m talking about are quarter notes, eighth notes, eighth note triplets, and sixteenth notes. For this lesson we’ll use a jam track that is just drums at 70 beats per minute. If you want to use a metronome instead, that’s okay too.

This loop is in 4/4 time and you’ll be able to count along with it the same way I do in the video. Those numbers are the quarter notes, which are the basic beat and pulse. You can strum along with the quarter notes using all downstrokes or alternating down and upstrokes. Either way, being able to follow a beat is the first step following this exercise and developing your timing.

Listen to the drumbeat in the jam track, try to lock in to be right on beat, and have all your strums spaced evenly. Check out the video to see me play a sample, and then work on this exercise until you feel very comfortable staying on the beat. You can also pull out a metronome to practice locking in on the beat at different tempos. One tip for you here is that moving another part of your body like nodding your head or tapping your foot can help you stay in time.

The next step in our exercise is to switch from quarter notes to eighth notes. If you’re not familiar with eighth notes, you’re essentially taking quarter notes and doubling the amount of strumming you’ll do. Quarter counts are counted by ‘1, 2, 3, 4,’ where eighth notes are counted by ‘1, and, 2, and, 3, and, 4, and,’ which doubles your strumming.

When you transition from quarter notes to eighth notes, there’s a chance you’ll start dragging behind or rushing ahead of the beat, so make sure to keep listening for the beat. Keep yourself locked into the beat and make sure your strumming is still evenly spaced.

When you start playing eighth notes, I’d recommend alternating upstrokes and downstrokes as it’s easier to keep up with the beat. In the video, I play an example starting with quarter notes, switching to eighth notes, and going back to quarter notes. As you try it, you can stick with each subdivision for as long as you like.

If you’ve made it this far with me on this exercise, you’re doing a great job. Now we’re moving to the tricky part of the exercise, eighth note triplets. Eighth note triplets are three evenly spaced strums per beat. If you’ve never counted triplets before, it can be a bit tricky. It’s counted as ‘1-trip-let, 2-trip-let, 3-trip-let, 4-trip-let,’ meaning there are three syllable for each beat.

If you’re having trouble playing eighth note triplets, you can spend some time just tapping it out like I do in the video. Another thing you’ll need to watch out for is not accidentally playing two short notes and a long note, but still keeping your strums spaced out evenly.

Since you have three strums per beat, note that you’ll start with a down up down on the first beat and the next beat will up down up. Because three is an odd number, one beat will start on a down stroke and the next beat will start with an upstroke.

Let’s add this triplet to our exercise. Go through quarter notes for as many measures as you like, switch to eighth notes, and then go to eighth note triplets. When you switch to the triplets, you’ll probably have some rushing or dragging, but that is normal at first since the triplets have a much different feel from the other subdivisions. In the video, you can check out how it will sound from my example.

The final subdivision in our exercise is sixteenth notes, and you’ve probably already guessed that sixteenth notes are four evenly spaced strums per beat. Sixteenth notes are counted as ‘1-e-and-a 2-e-and-a 3-e-and-a 4-e-and-a ’ giving us four distinct syllables for each beat.

if this is tough for you to play at first, just try tapping it out like I do in the video. Once you’re comfortable with these sixteenth notes, we want to add them to the exercise. Play through quarter notes, eighth notes, eighth note triplets, sixteenth notes, and then work your way back down to quarter notes. Remember that moving your head or tapping your foot to the beat will help you keep time. Check out the video for my sample of this exercise with sixteenth notes added in.

The point of this exercise is to help you be aware of the beat and be able to switch between subdivisions in a moment’s notice. If you can get this down, it will sharpen your rhythm and set you apart from a lot of other guitar players.

I know this is a lot of information, so don’t feel pressured to have all these subdivisions down in one exercise. You can start out with just quarter notes and eighth notes, and after you’re comfortable with those you can add in eighth note triplets. Once you’re comfortable with eighth note triplets, then you can add in sixteenth notes.

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)