Saturday, April 11, 2015

How To Play Major Bar Chord Shapes

Before learning the new chord shape, take a look at the graphic on-screen to see the names of the notes on the A string. Those are going to be the root notes for this bar chord shape.

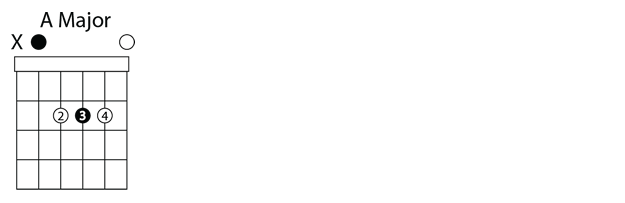

We’re going to start learning this shape by making an open A chord, because that’s the foundation of this bar chord. Just like the other bar chord you’ve learned, we need to make this shape with our second, third, and fourth fingers. All three fingers will be on the second fret, with your second finger on the D string, third finger on the G string, and fourth finger on the B string. Leave the low E string out, and strum just the top five strings. This will feel different from what you’re used to, so it may take a bit for it to seem natural.

Once you’ve got that shape down, you need to come down with your index finger to make a bar right on the nut of the guitar. Take time here to get used to the whole shape and how it feels.

When you’re comfortable with the shape, move your bar up to the third fret and make your bar chord shape. Remember all the tips from video four about making a good sounding bar. Make your bar right behind the fret, come down with the bony edge of your finger, and adjust your bar vertically on the strings to get the cleanest sound.

When I’m making a five-string bar chord like this, I won’t always fret the sixth string, but my index finger will brush up against the string to mute it in case I accidentally hit it while strumming.

After your bar is in place on the third fret, come down on the strings with your second, third, ad fourth fingers to make the rest of your A shape. Now play the top five strings, leaving the sixth string out.

Once you’ve tried it, ask yourself if your bar chord sounded clean or if it sounded a little dead. If it was sounding dead or muted, double-check yourself. Make sure you’re coming down on the strings with the tips of your fingers and make sure your bar is strong behind the fret.

With this shape, you can train yourself in a couple of different ways again. Try putting your bar on first, followed by the rest of the shape, and then do the opposite by making your shape first and then the bar. Eventually, you’ll be comfortable enough to make this bar chord all at once.

After you’ve mastered this bar chord shape, you can try an alternate way of making it. You can use your third finger like a mini bar to hit all three strings in the A shape. It feels a little different and is a bit harder, but it’s another fingering method you can try out.

Play with this shape and practice by moving it all around the fretboard. Remember that the lowest note you play on the fifth string with your index finger is where you’ll get the specific name for each bar chord you’re playing. By getting familiar with the graphic on-screen you’ll know that a bar on the third fret makes a C bar chord, while being on the fifth fret would make a D bar chord.

Once you’re comfortable with this bar chord shape, you’ll need to start mixing it up with your sixth string shape, the E major bar chord. Just like the power chords we learned, this will keep you from having to jump all the way up and down the fretboard. As an example, playing a G-C-D progression on only the sixth strings means I’m moving around a lot. By using both sixth and fifth string bar chords, you see in the video that I have an easier time playing that chord progression.

You’ll need to get comfortable moving from the E shaped bar chord to the A shaped bar chord. That back and forth switch is a really important change every rhythm guitarist should have down. Using sixth and fifth bar string bar chords keeps you from jumping around the fretboard too much and helps you play a lot more efficiently.

Be sure to take enough time getting comfortable with each shape though before trying to switch between them. If you rush switching between bar chords before you’re ready, you’ll cause yourself a lot of frustration. Once you really have the shapes down, it will be easier to switch between them.

Now you need to apply this to some real music, so you can pull up the jam track for this lesson again. It is a G-C-D progression, and it’s one measure for each chord. You can keep it simple by playing a whole notes and concentrating on making your chords and changes well, or you can play quarter notes for every chord. You can check out my example of playing with the jam track in the video.

The guitar is an ancient and noble instrument, whose history can be traced back over 4000 years. Many theories have been advanced about the instrument's ancestry. It has often been claimed that the guitar is a development of the lute, or even of the ancient Greek kithara. Research done by Dr. Michael Kasha in the 1960's showed these claims to be without merit. He showed that the lute is a result of a separate line of development, sharing common ancestors with the guitar, but having had no influence on its evolution. The influence in the opposite direction is undeniable, however - the guitar's immediate forefathers were a major influence on the development of the fretted lute from the fretless oud which the Moors brought with them to to Spain.

The sole "evidence" for the kithara theory is the similarity between the greek word "kithara" and the Spanish word "quitarra". It is hard to imagine how the guitar could have evolved from the kithara, which was a completely different type of instrument - namely a square-framed lap harp, or "lyre".

It would also be passing strange if a square-framed seven-string lap harp had given its name to the early Spanish 4-string "quitarra". Dr. Kasha turns the question around and asks where the Greeks got the name "kithara", and points out that the earliest Greek kitharas had only 4 strings when they were introduced from abroad. He surmises that the Greeks hellenified the old Persian name for a 4-stringed instrument, "chartar". The earliest stringed instruments known to archaeologists are bowl harps and tanburs. Since prehistory people have made bowl harps using tortoise shells and calabashes as resonators, with a bent stick for a neck and one or more gut or silk strings. The world's museums contain many such "harps" from the ancient Sumerian, Babylonian, and Egyptian civilisations. Around 2500 - 2000 CE more advanced harps, such as the opulently carved 11-stringed instrument with gold decoration found in Queen Shub-Ad's tomb, started to appear.A tanbur is defined as "a long-necked stringed instrument with a small egg- or pear-shaped body, with an arched or round back, usually with a soundboard of wood or hide, and a long, straight neck". The tanbur probably developed from the bowl harp as the neck was straightened out to allow the string/s to be pressed down to create more notes. Tomb paintings and stone carvings in Egypt testify to the fact that harps and tanburs (together with flutes and percussion instruments) were being played in ensemble 3500 - 4000 years ago.At around the same time that Torres started making his breakthrough fan-braced guitars in Spain, German immigrants to the USA - among them Christian Fredrich Martin - had begun making guitars with X-braced tops. Steel strings first became widely available in around 1900. Steel strings offered the promise of much louder guitars, but the increased tension was too much for the Torres-style fan-braced top. A beefed-up X-brace proved equal to the job, and quickly became the industry standard for the flat-top steel string guitar.

At the end of the 19th century Orville Gibson was building archtop guitars with oval sound holes. He married the steel-string guitar with a body constructed more like a cello, where the bridge exerts no torque on the top, only pressure straight down. This allows the top to vibrate more freely, and thus produce more volume. In the early 1920's designer Lloyd Loar joined Gibson, and refined the archtop "jazz" guitar into its now familiar form with f-holes, floating bridge and cello-type tailpiece.

The electric guitar was born when pickups were added to Hawaiian and "jazz" guitars in the late 1920's, but met with little success before 1936, when Gibson introduced the ES150 model, which Charlie Christian made famous.

With the advent of amplification it became possible to do away with the soundbox altogether. In the late 1930's and early 1940's several actors were experimenting along these lines, and controversy still exists as to whether Les Paul, Leo Fender, Paul Bigsby or O.W. Appleton constructed the very first solid-body guitar. Be that as it may, the solid-body electric guitar was here to stay.

The sole "evidence" for the kithara theory is the similarity between the greek word "kithara" and the Spanish word "quitarra". It is hard to imagine how the guitar could have evolved from the kithara, which was a completely different type of instrument - namely a square-framed lap harp, or "lyre".

It would also be passing strange if a square-framed seven-string lap harp had given its name to the early Spanish 4-string "quitarra". Dr. Kasha turns the question around and asks where the Greeks got the name "kithara", and points out that the earliest Greek kitharas had only 4 strings when they were introduced from abroad. He surmises that the Greeks hellenified the old Persian name for a 4-stringed instrument, "chartar". The earliest stringed instruments known to archaeologists are bowl harps and tanburs. Since prehistory people have made bowl harps using tortoise shells and calabashes as resonators, with a bent stick for a neck and one or more gut or silk strings. The world's museums contain many such "harps" from the ancient Sumerian, Babylonian, and Egyptian civilisations. Around 2500 - 2000 CE more advanced harps, such as the opulently carved 11-stringed instrument with gold decoration found in Queen Shub-Ad's tomb, started to appear.A tanbur is defined as "a long-necked stringed instrument with a small egg- or pear-shaped body, with an arched or round back, usually with a soundboard of wood or hide, and a long, straight neck". The tanbur probably developed from the bowl harp as the neck was straightened out to allow the string/s to be pressed down to create more notes. Tomb paintings and stone carvings in Egypt testify to the fact that harps and tanburs (together with flutes and percussion instruments) were being played in ensemble 3500 - 4000 years ago.At around the same time that Torres started making his breakthrough fan-braced guitars in Spain, German immigrants to the USA - among them Christian Fredrich Martin - had begun making guitars with X-braced tops. Steel strings first became widely available in around 1900. Steel strings offered the promise of much louder guitars, but the increased tension was too much for the Torres-style fan-braced top. A beefed-up X-brace proved equal to the job, and quickly became the industry standard for the flat-top steel string guitar.

At the end of the 19th century Orville Gibson was building archtop guitars with oval sound holes. He married the steel-string guitar with a body constructed more like a cello, where the bridge exerts no torque on the top, only pressure straight down. This allows the top to vibrate more freely, and thus produce more volume. In the early 1920's designer Lloyd Loar joined Gibson, and refined the archtop "jazz" guitar into its now familiar form with f-holes, floating bridge and cello-type tailpiece.

The electric guitar was born when pickups were added to Hawaiian and "jazz" guitars in the late 1920's, but met with little success before 1936, when Gibson introduced the ES150 model, which Charlie Christian made famous.

With the advent of amplification it became possible to do away with the soundbox altogether. In the late 1930's and early 1940's several actors were experimenting along these lines, and controversy still exists as to whether Les Paul, Leo Fender, Paul Bigsby or O.W. Appleton constructed the very first solid-body guitar. Be that as it may, the solid-body electric guitar was here to stay.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments

(

Atom

)

No comments :

Post a Comment